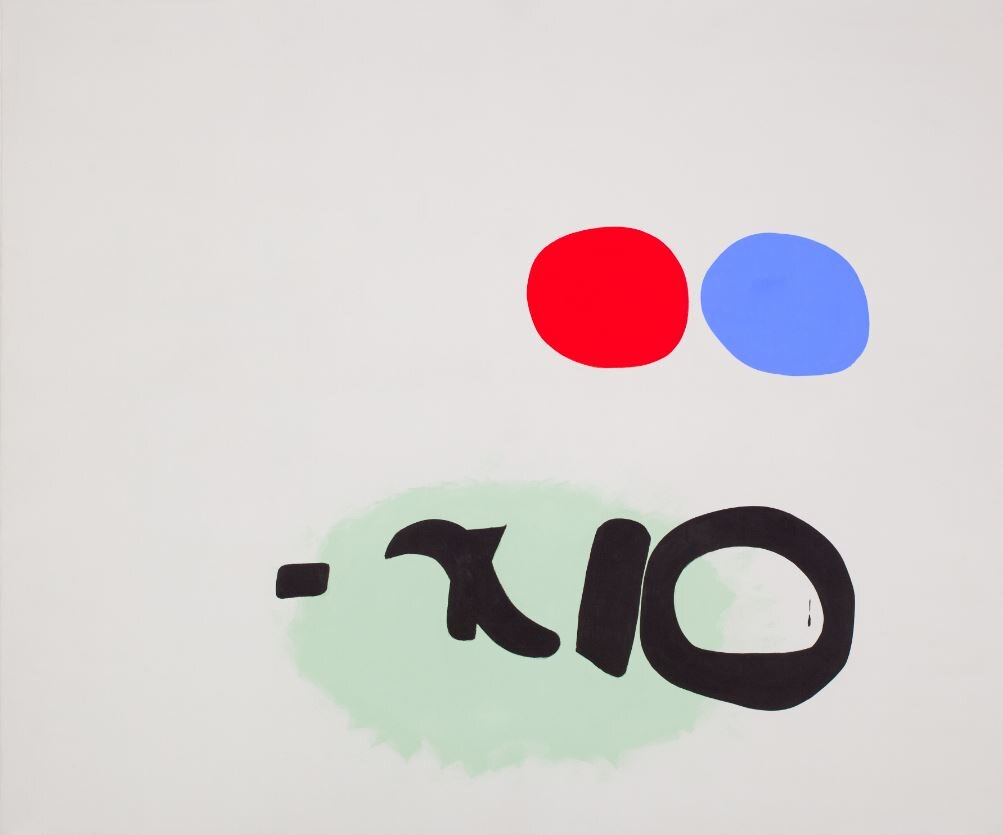

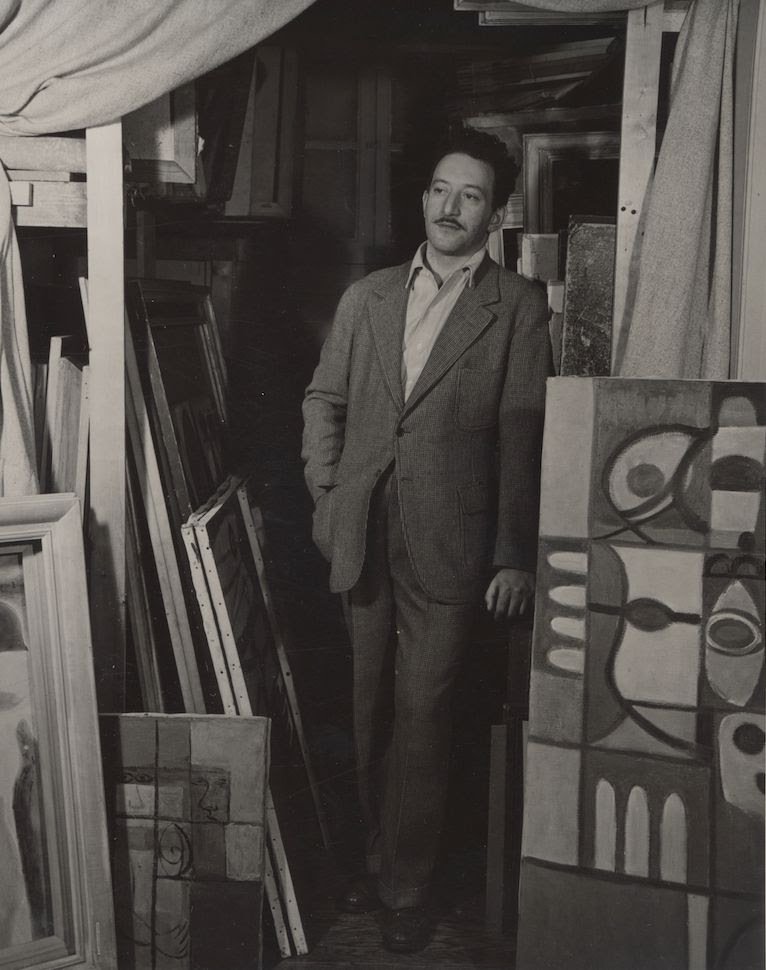

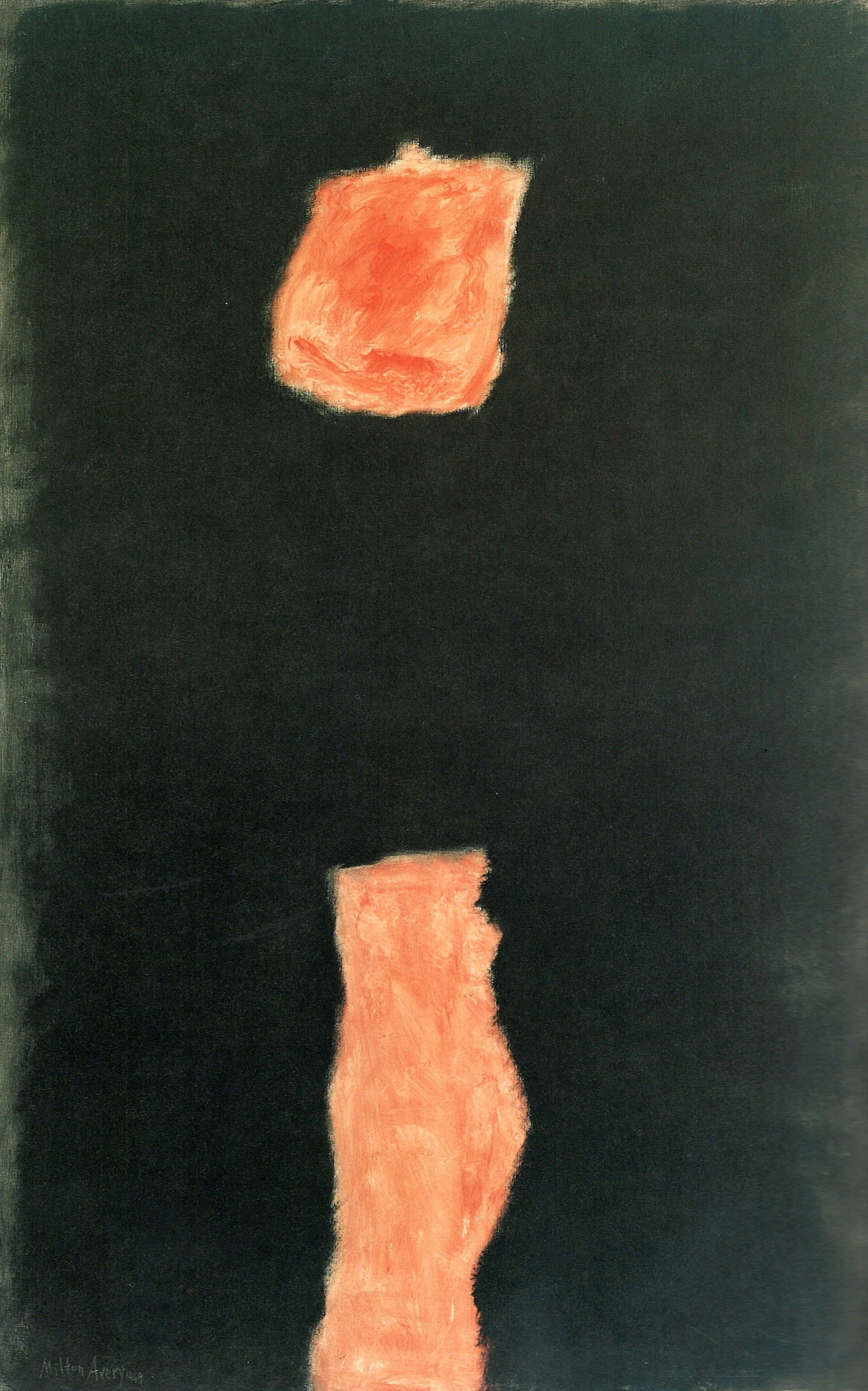

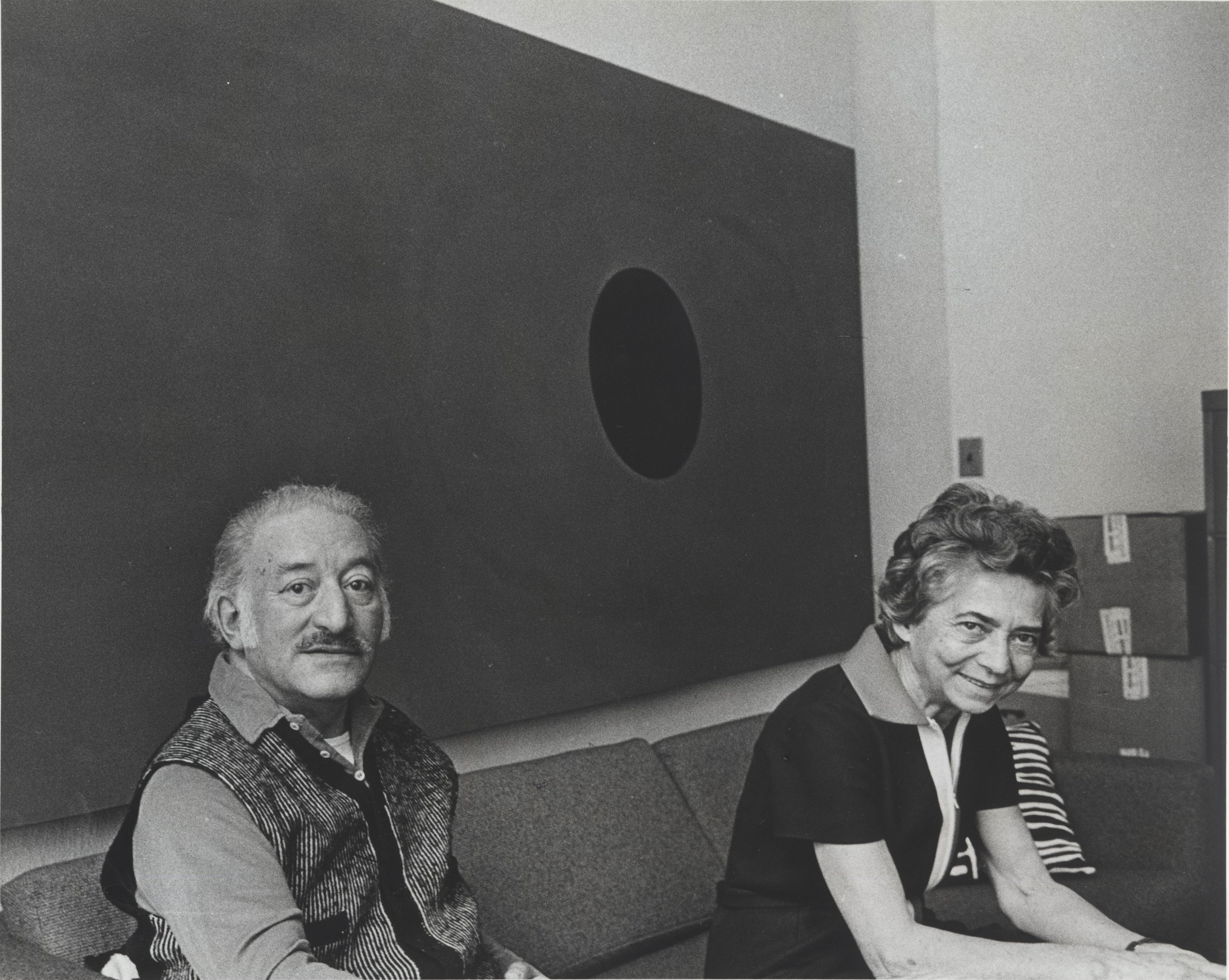

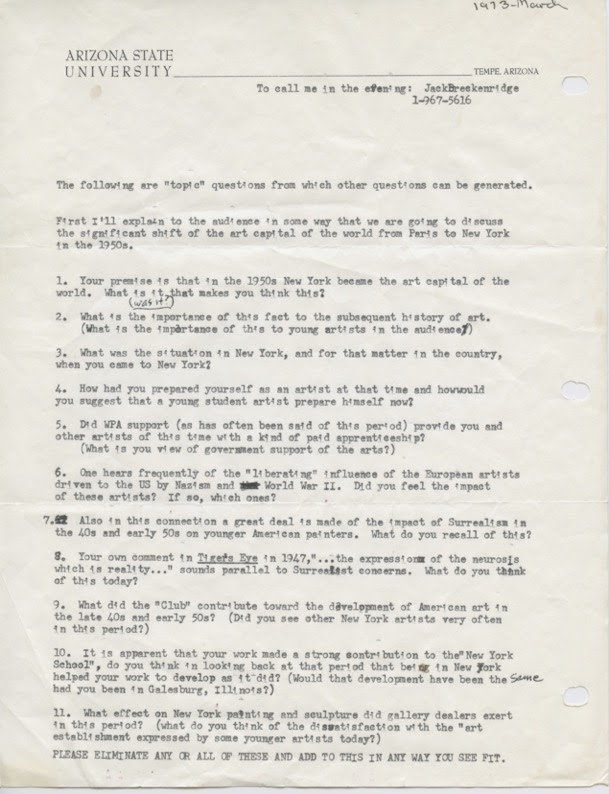

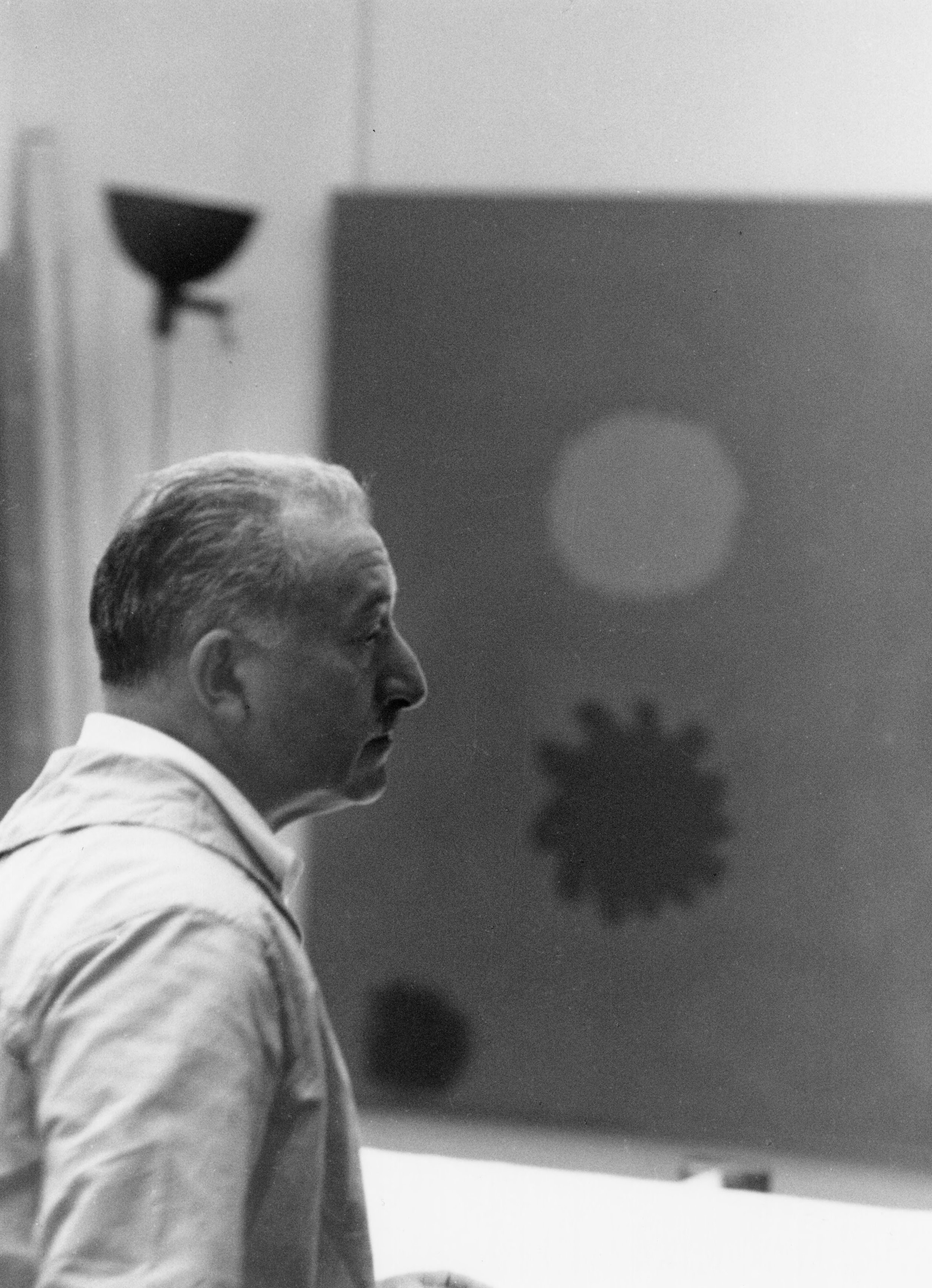

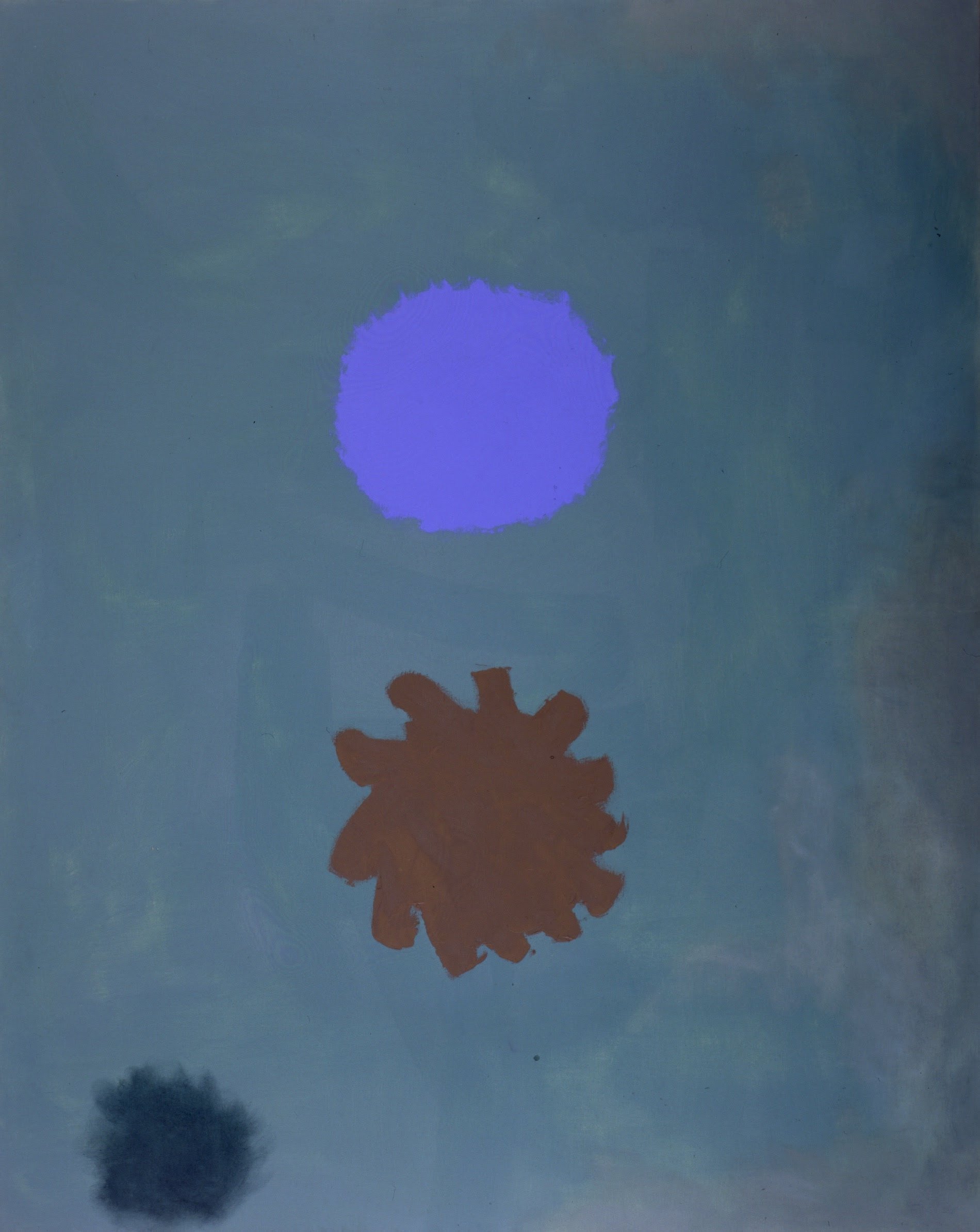

Adolph Gottlieb (AG): There is something I would like to get across to you – it has to do with the different atmosphere and when I was young – as you may know, during the Forties most of us in New York were doing all-over painting. There was something in the air that made us do that. I don’t know how to explain it, but we felt that was the way painting was going. It was all-over, there was no beginning and no end. I decided that I was tired of the paintings which were endless: which were all-over paintings. I decided that I would try to make paintings which had a focal point very much the way a portrait had. All of the paintings that were done after the Forties have that characteristic and I still retain that. As you can see there is a very defined focal point.

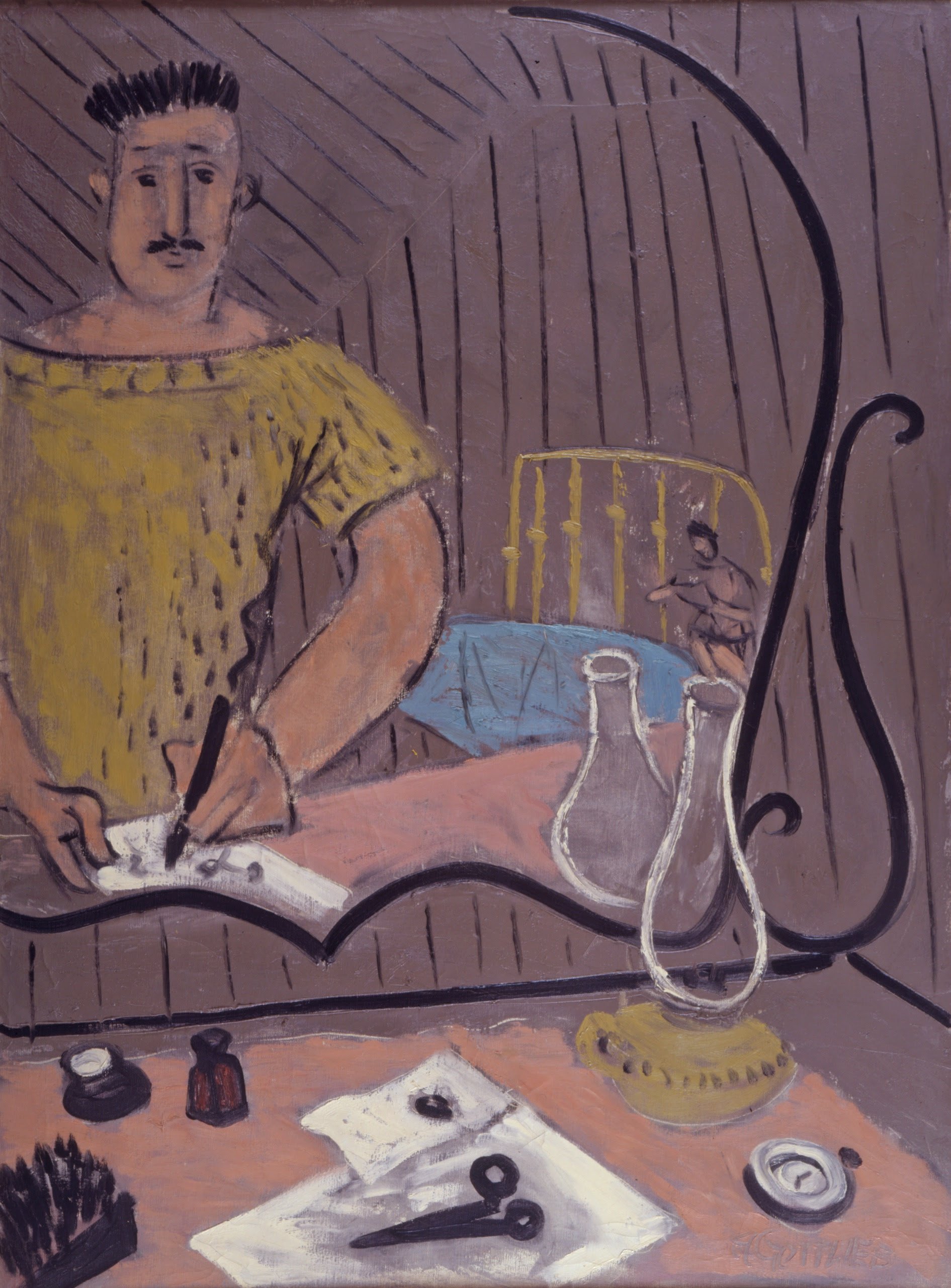

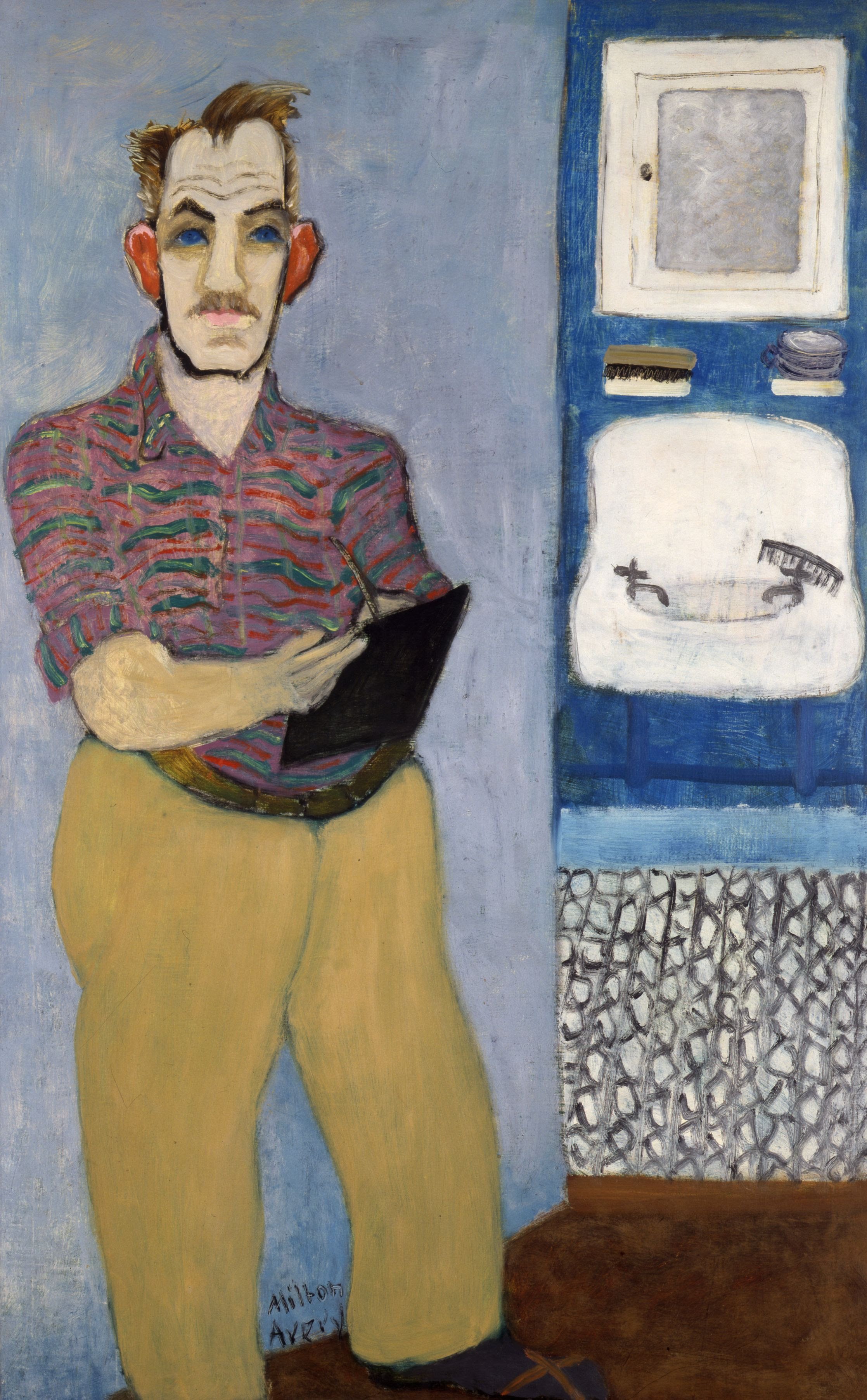

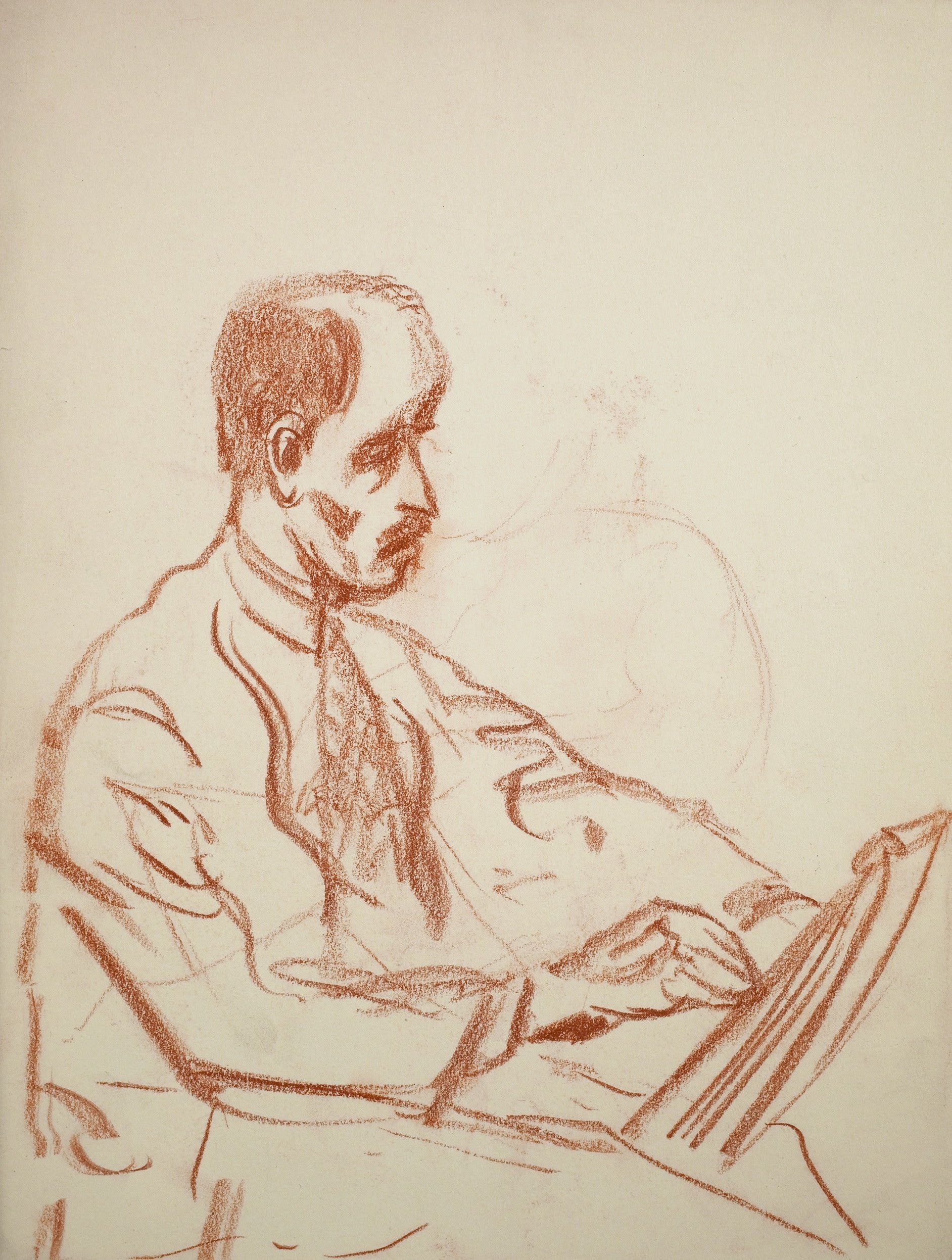

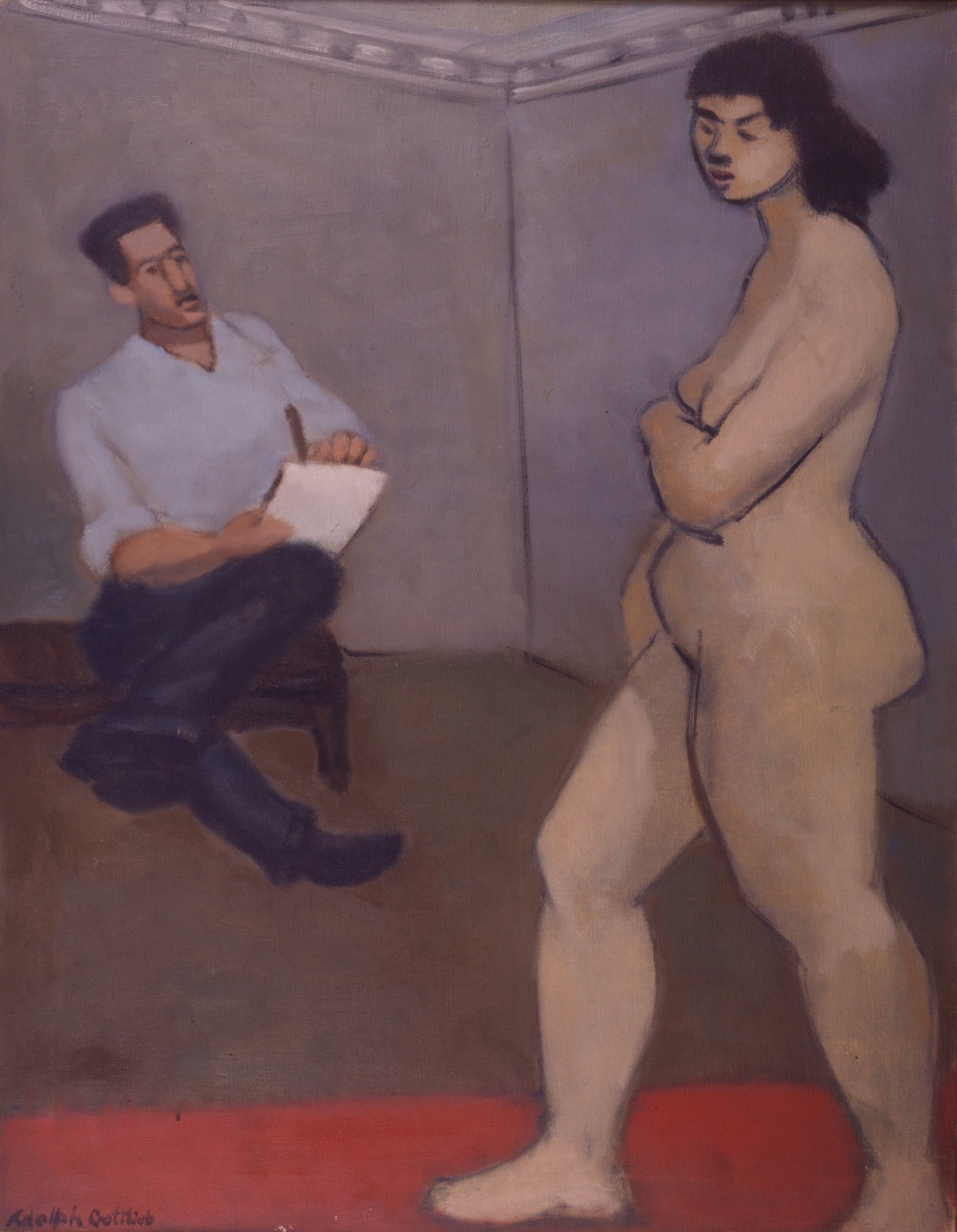

I must say that I am not prepared to make a lecture in the usual sense that we are accustomed to. I don’t have the pedagogical approach. I think it is my prerogative as an old man to reminisce and go back to early days. I’ll have a lot of loose ends which I hope will tie together. I think that you will find that they will tie together. I’ll just go back to when I went to Europe for the first time in 1921. I worked my way over on the ship and had a lot of adventures which are another story. I eventually got to Paris and I did very little painting. I was going to the Grand Chaumiere to a sketch class where I did sketches from life. While the instructor was supposed to be Lucien Simon, I never saw Mr. Simon. I just went and worked on my own. And I did something that was more useful, I went to the Louvre almost every day. I certainly went there every other day. I knew the Louvre very well. I could go in there and find my way to any painting that I was interested in seeing. I think this was the best experience that I could possibly have had because I think that the real university for any young artist is the museum which has a rich collection. I think it is much better to study with Poussin than study with Gottlieb. So you see in a sense I am very modest. At any rate, what I wanted to say was that those days were the days of the expatriates like Hemingway and others and it was considered to be very important to go to Europe for an America artist. American art at that point was – well, it was very much behind – about twenty-five years behind European art. The European Impressionists were about twenty-five years ahead of the American Impressionists. In fact, at that time American artists were waiting for the latest copy of Cahiers d’Art to see what was happening in Europe and that gave them a cue as to how to proceed. So I went to Europe and the best thing was the museum.

Jack Brekenridge (JB): What would you say to the young student who wishes to train himself today?

AG: Today I would say that he should go to New York and haunt the Metropolitan and other museums.

JB: And not worry about the Art Students’ League?

AG: No, I don’t think the Art Students’ League would do him much good.

JB: You talked to me the other day about the importance of the shift of the art capital from Paris to New York.

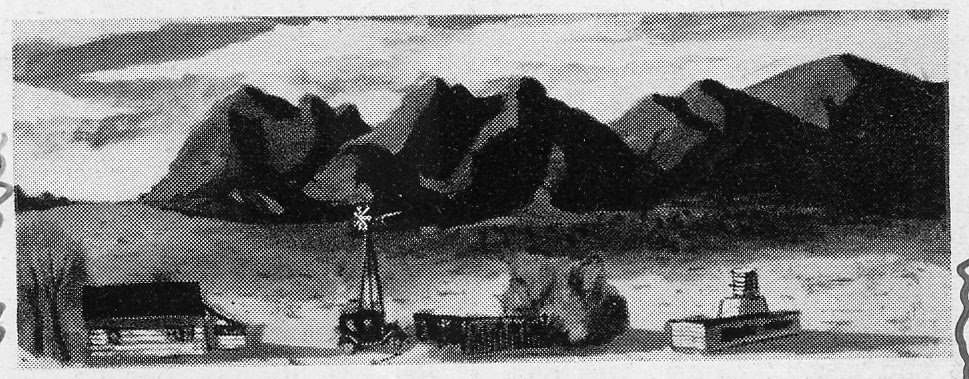

AG: Well, I am very interested in that. I’ll explain it to you. When I went to Paris and I lived in Europe for awhile I became a Francophile. There are many great French artists whom I admired so much that they impressed me for my whole life – older artists like Ingres, Delacroix, and Courbet. When I came back to New York I found there was a very deeply ingrained provincialism in the United States which seemed to stem from the Midwest and with it came a great deal of Midwestern painting that I thought was very bad. I’m talking about Benton, Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry. I think that, in a way, they created a vacuum into which the next generation could step.

JB: By being so bad?

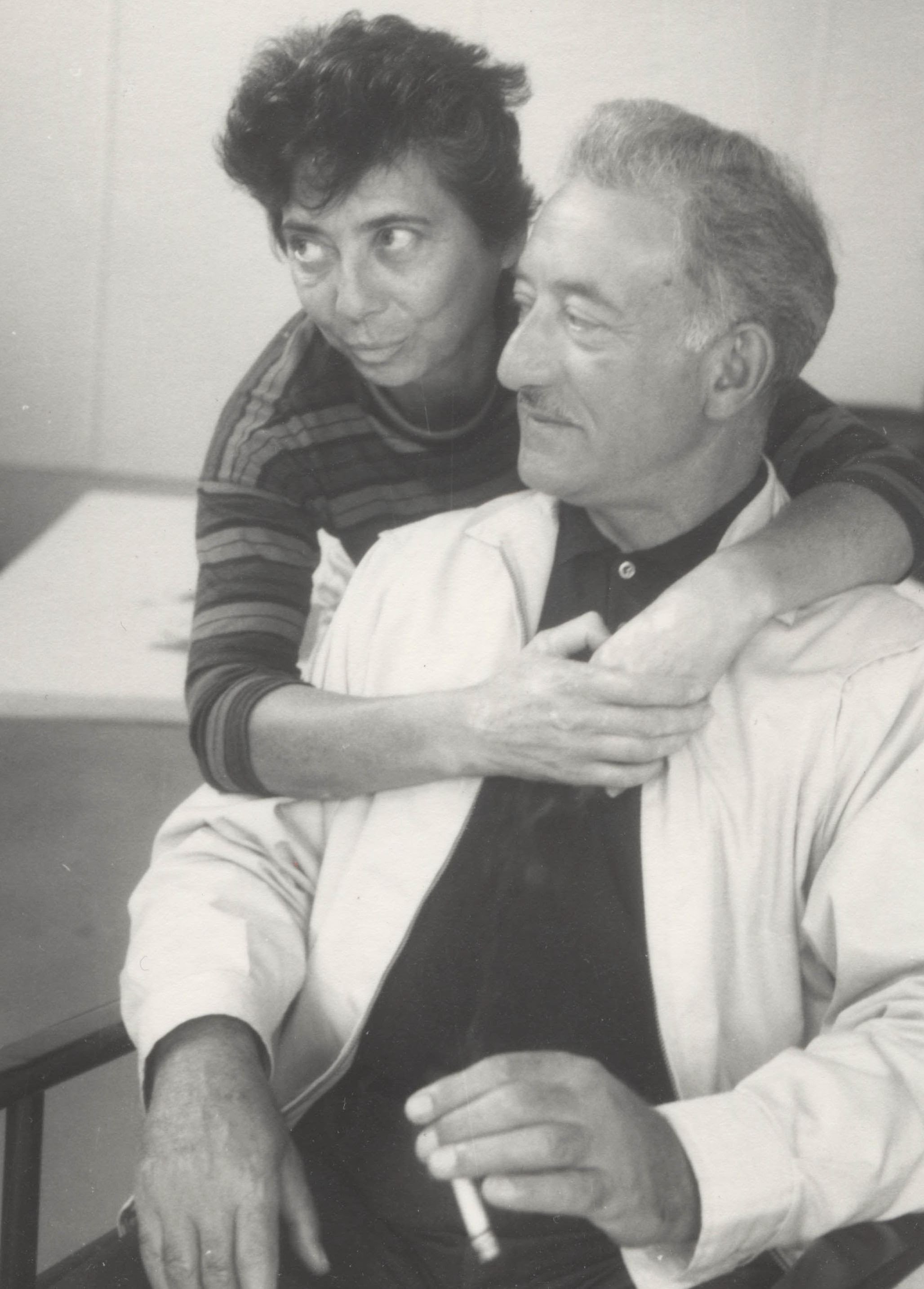

AG: That’s right – and I think that I should tell you that in the Forties there was a lot of talk among New York artists as to whether New York was going to be the art capital of the world. As a personal reminiscence my wife and I used to go to Provincetown in the summers in those days and in the summer of 1949 between my wife and myself and a friend of ours named Weldon Kees, who was a very sensitive poet and painter, and Fritz Bultman, who was painter and sculptor, we started something called Forum Forty-Nine. In the course of the summer we had a number of interesting exhibits and forums. The forums and exhibits took place in an old, no-longer-used post office that we got the use of. Each of us took turns in organizing something and my turn came up, so I organized a forum called “French Art versus American Art”. This created quite a bit of dissension. We didn’t have any exhibit of French art, we had a discussion. We did show the American artists who were in Provincetown at the time. We invited a number of distinguished people to this forum, among them were Stuart Preston of the New York Times and Fred Wight, who now, I think, heads the art department at UCLA. Before the forum started there were a group of dissidents including Hans Hofmann and Fritz Bultman who wanted to hand out a mimeographed flyer to people who were coming in. So we said to them, “Don’t hand it out, we’ll give it to everyone who buys a ticket.” The flyer read something to the effect that “…we are objecting to this program because we consider Paris the city of light and culture and light and culture have emanated from it for the past hundred years or more, so we are in disagreement with this topic.” We then handed it out to everybody. After the forum there was a party at someone’s house. While we were at the party, I went over to Hofmann. I said, “Hans what did you really object to about this forum? Now that you’ve heard it don’t you think that it was all right? It was an interesting discussion.” He said, “Well, I’ll tell you Adolph, you should have French art first.” I asked, “Why?” He replied, “Because French art is better than American art.” So I said, “We did say ‘French Art versus American’.” He said, “Well, then it’s all right.”

JB: Then, there was evidence in your mind, by 1949 that…

AG: Oh, by 1949 we were afraid that we were being too chauvinistic about American art. So the question came up, were we right in being too chauvinistic? I took the position that we were entitled to it because as I saw it – well, I’ll give you an example of what I mean. I was in the Kootz Gallery one time and I was in this back private viewing room. This was in the middle Forties or late Forties. Kootz had just been to Paris and had brought back one of the latest paintings of a young Parisian painter. To show it to this collector, he put it on a chair. Then the collector, to look at it more closely got down and looked at it very closely, in fact, his knee touched the floor and I thought it was very symbolic – down on his knees before a French painting, because it was French. He would never had done that for a new American painting. At that point I decided that chauvinism was good for us.

JB: What do you think that this had meant to younger artists?

AG: I think that it has given great freedom. As an example of what I mean, I was on a broadcast with a British critic – the broadcast was supposed to be for the BBC – and I made a point about this. I was discussing this business about American art in relation to European art and the ways it had been subservient to it. I said that France was like a colonial power in art and that we were the colonists; and that in the 1940s American artists took the tea and dumped it overboard and had their Declaration of Independence. I was curious to see how this would go over with the British. I later saw a transcript and they cut that out. I think the situation got reversed and America became the colonial power artistically. The Japanese and many others, including the French, became our subjects.

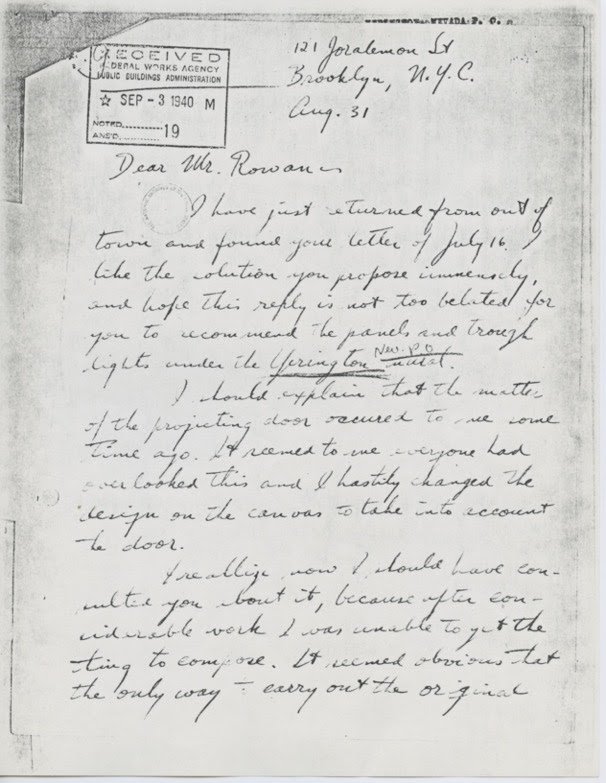

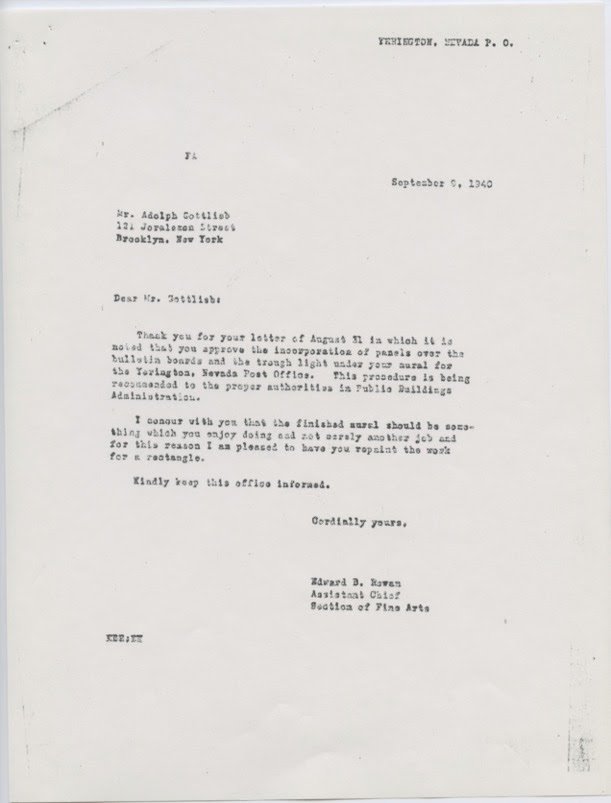

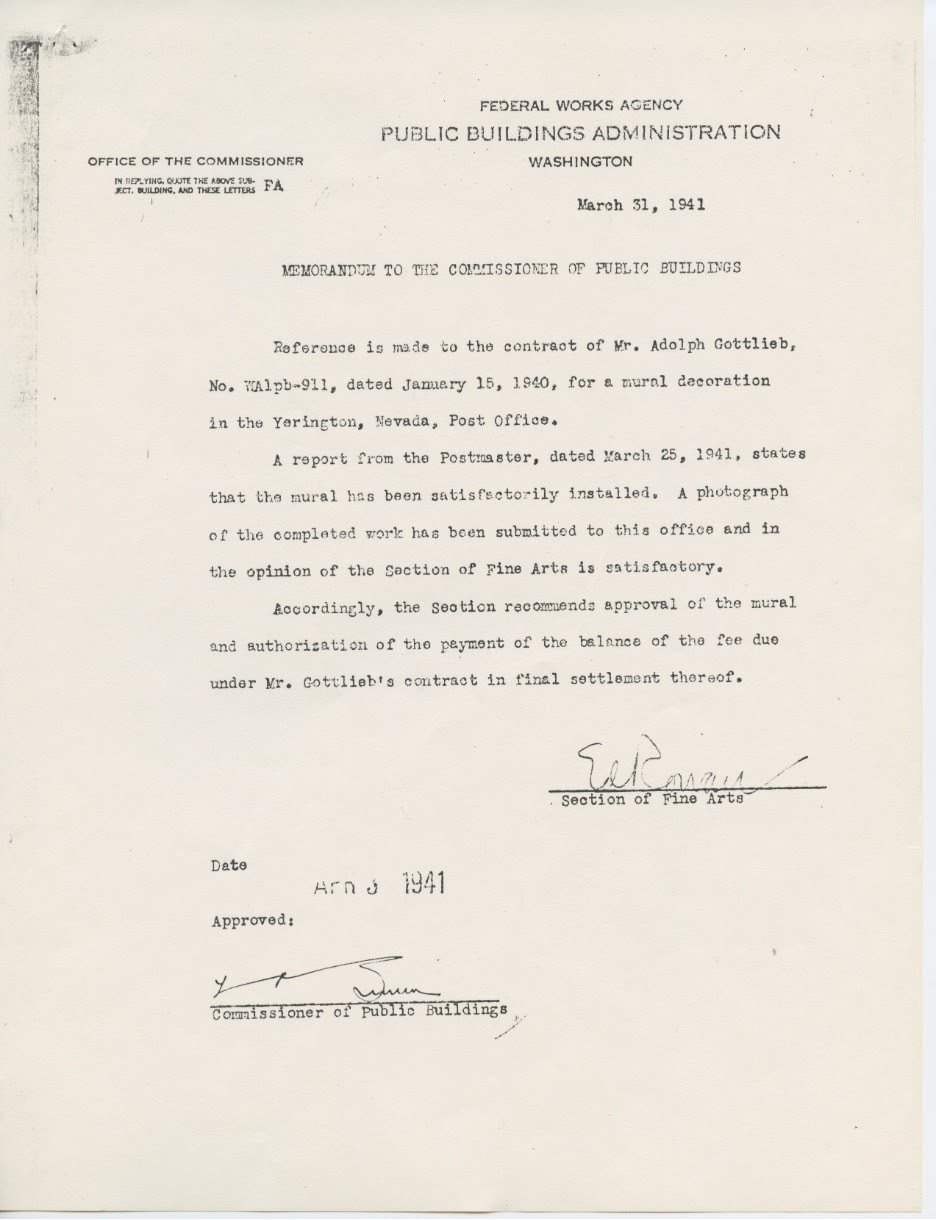

JB: Let’s talk about the WPA. You worked for a time for the WPA?

AG: I did, yes. I think it was $23.50 a week.

JB: A lot of people have said that this was a kind of apprenticeship for young artists of that time.

AG: I think the value of the WPA is vastly exaggerated.

JB: What do you think, then, of government support of the arts?

AG: I think it is very dangerous. It has a tendency to try to influence the artist. Just like dealers try to influence artists.

JB: Have they tried to influence you?

AG: Yes. Oh sure. Either to maintain a style or to get certain qualities that they like or that they think are saleable.

JB: Do you believe that the dealer system is a bad system?

AG: No, I think that it is the best system that we have.

JB: Then you don’t agree with the dissatisfied younger artists in New York. There are a number of dissatisfied young artists –

AG: Oh, yes, but in many cases it is a matter of sour grapes. They can’t seem to adapt to the dealer system so they want to abolish it.

JB: How do younger painters go about breaking into the system?

AG: They have to make a little name for themselves among the New York artists. To be there, to be in group shows, and be part of the give and take.

JB: Then someone is not going to walk in from off the streets and knock the dealer dead with his work?

AG: No, that’s very hard. The dealers are very jaded. They have so many artists come in everyday and show them work. They can assume before hand that it will be no good.

JB: We talked earlier about the “give and take” among artist, were you talking about something like that which went on in the Club in the late 1940s?

AG: Like the Club – where artists would express their views about what a painting should be and what it is, and others could attack.

JB: Where did you meet?

AG: We met in an empty loft on Eight Street. Sometimes we would visit in other artists’ studios and say whatever we thought.

JB: You just spoke right out?

AG: Well, we were friends.

JB: Do you still have a close association with many of those artists today?

AG: I don’t. Most of us sort of outgrew this.

JB: There has been a good deal of talk about the influence in New York in the Forties of Europeans who arrived because of the war. People like Leger, Mondrian, Lipshitz, and others.

AG: Yes, I met a number of them.

JB: Do you feel that they exerted any kind of influence on American art or do you think that things had already been solidified by that time?

AG: I think that by that time Surrealism was a definite influence on American art because the work was being shown in New York by various dealers. Then when the artists came over that showed us that they were just people like we were.

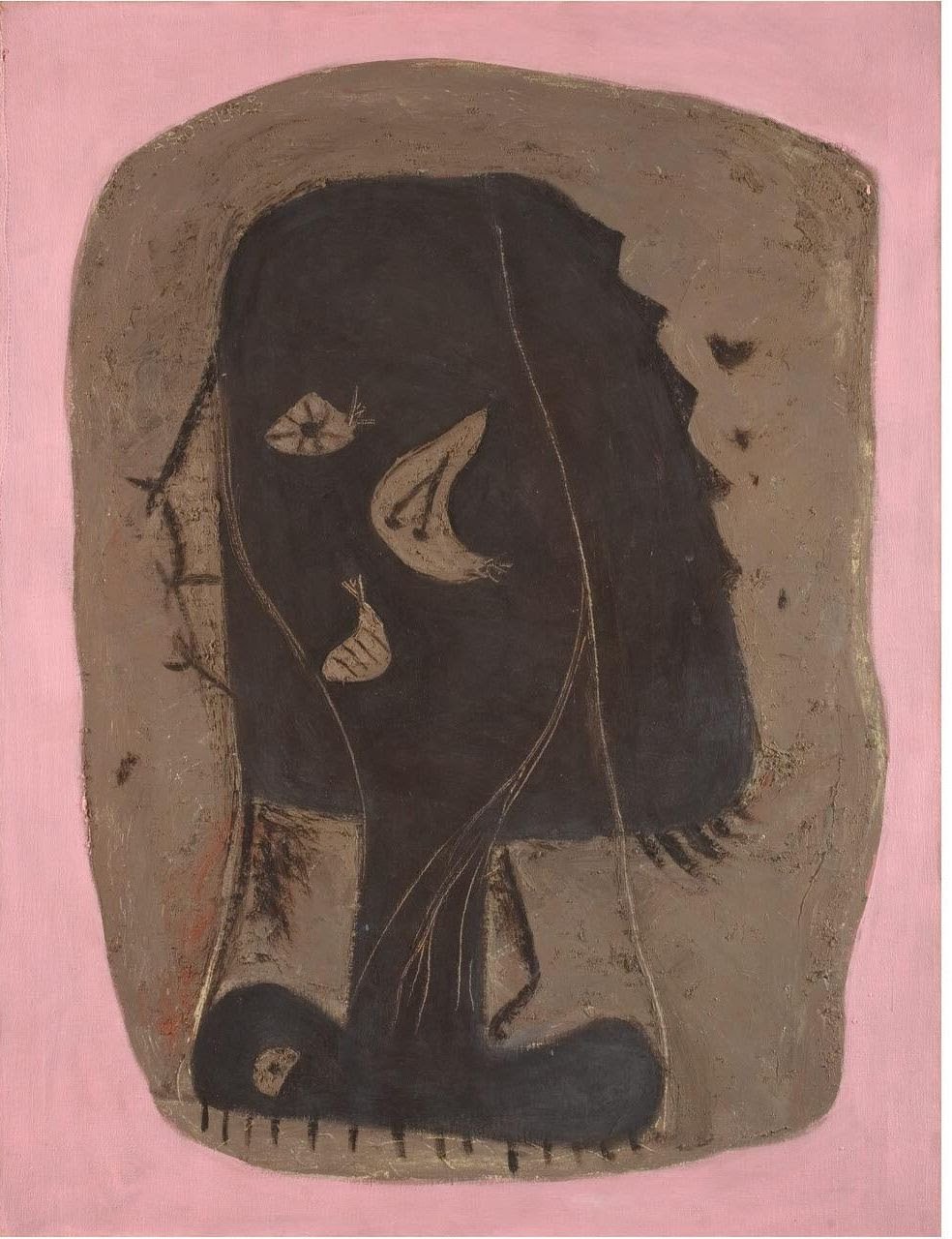

JB: Do you feel that there was an impact of Surrealism on your work during this period?

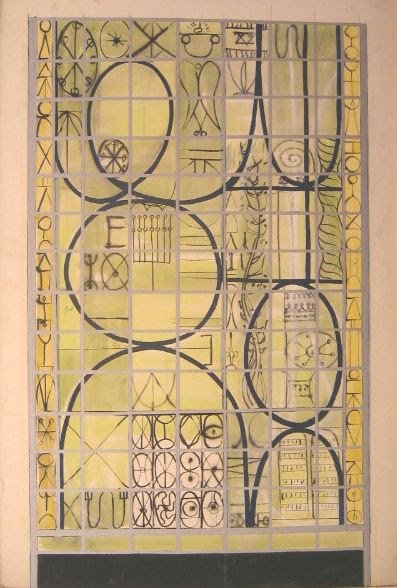

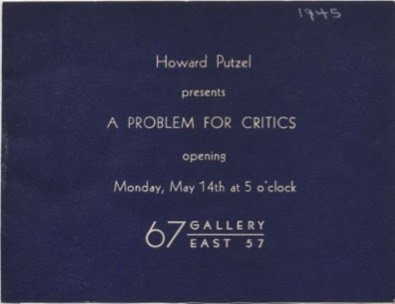

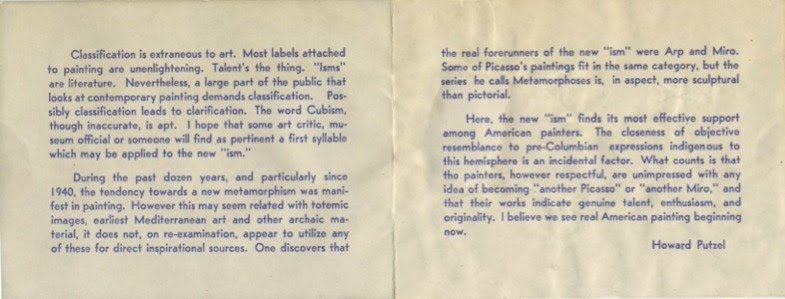

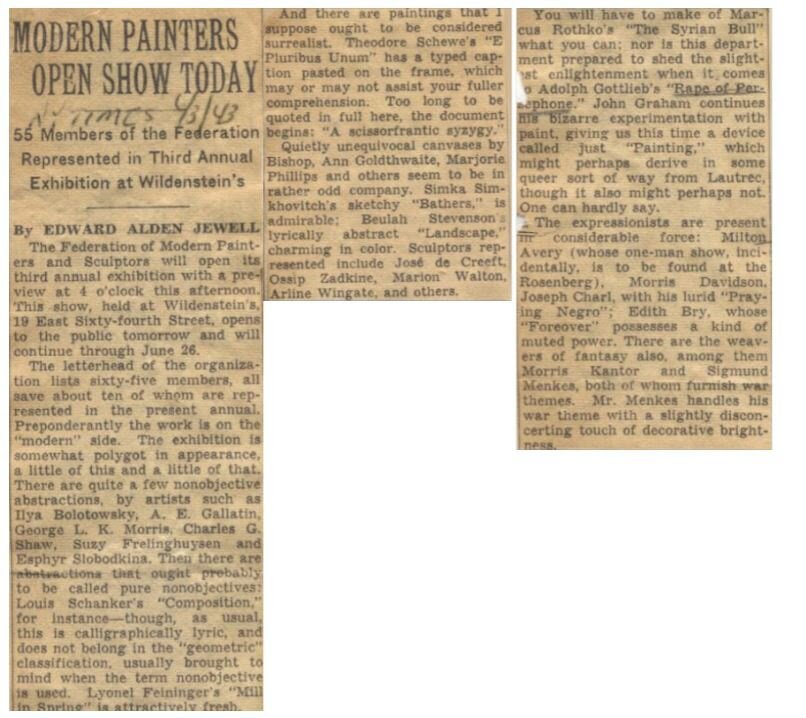

AG: Yes, I think so – definitely. There was a gallery in New York called Gallery Sixty-Seven. It had a show called “A Problem for Critics.” It included my work, Pollock’s, Rothko’s, Hofmann’s, and a number of others. The problem was how to characterize this work. Most of it had Surrealist influence. A lot of it had Cubist influence. I felt that the work we all were doing was kind of a merger of both – Surrealism and abstraction.