Shown: Martin Friedman standing in front of Trio (1960) by Adolph Gottlieb.

Adolph Gottlieb: Recent Paintings at The Walker Art Center in 1963

In 1963, Martin Friedman, Director of the Walker Art Center, organized an exhibition of Adolph Gottlieb's recent work at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The organization of this exhibition began a long friendship and working relationship between Friedman and Gottlieb. Below is a selection of archival material to document their relationship and the 1963 exhibition.

Shown: A letter to Adolph Gottlieb from Martin Friedman outlining the plans for the 1963 exhibition of Gottlieb's work, June 18, 1962.

An Interview with Adolph Gottlieb in August 1962:

In order to write and research his catalogue essay, Friedman arranged to interview Gottlieb in August 1962. Taking place over several days in Gottlieb's East Hampton home, Friedman conducted and recorded the interview. They discussed many topics from contemporary American painting to art-historical inspiration and the transition of Adolph's work throughout his career. This interview not only became the basis for Friedman's essay, but serves as a very thorough and deep look into Gottlieb's practice. Below are some excerpts from this interview conducted from August 10–13, 1962.

Gottlieb in the Early Years:

"I liked Parsons School of Design because my family felt that if I wanted to be an artist I should have some means of supporting myself and this was supposed to be some sort of a normal course to prepare me for teaching. But, I didn't finish because I didn't really want to teach. And, at a much later date, I reconsidered the matter and thought that perhaps I should after all go into teaching because I had, really, no source for earning my living; and I took the exam for teaching art in high school. And I passed the written part but I failed the drawing part, so I decided the hell with it, and never bothered again."

"I spent most of my time in Europe looking at paintings, looking at galleries, museums, and so forth. I did a bit of drawing and painting and sketch classes, but I had no formal instruction. At the Grande Chaumiere, there were sketch classes or you could paint from the model with or without instruction. I didn't take the instruction. I don't know why I did it –whatever the reasons were I don't recall, but in looking back on it I feel rather good about it because it was a period of absorption and it wasn't so necessary for me to learn the mechanics of painting or to learn any tricks."

Gottlieb on Pictographs:

"I felt that the symbols and images were private property and that the juxtaposition was in a sense quite arbitrary or at random or did occur by chance; and that this would then have to be seen as a total painting. You could begin at any point and look in every direction and keep going back and forth and every which way."

“The original notion that I had and the way I arrived at the pictograph stemmed from my great fondness for early Italian paintings in the 13th and 14th centuries. Altarpieces in which the life of Christ would be depicted in a series of sequences would be chronological– starting with the birth of Christ and going through his life to the resurrection, and this was somewhat of a comic strip technique– it was anecdotal and it was chronological."

Gottlieb on His Later Paintings:

"In the pictographs, the rectilinear areas, the divisions are somewhat arbitrary; they are not compositions in the traditional sense. By the same token, the framework of the imaginary landscape is also arbitrary. It starts out on the premise that I will divide the canvas into two areas. Then I also retain, as in the pictograph, interest in disparate shapes and finding some resolution for this disparity. I also have disparate shapes in the imaginary landscape. In other words, the shapes above are rounded and circular; the shapes below are linear and interlocking."

"In my recent work, I have rather calm, round shapes above and then a jagged space below. Well, there's no reason why these should be juxtaposed, except that it interests me to juxtapose things that are so different and are unrelated and I have to find some way of establishing relationships and bringing them together. I think that this sort of thinking took place in the pictograph, except in the pictograph, it wasn't boiled down as much to these two elements, or three elements. There were a great many elements involved there and it was this process of relating the unrelated wasn't pinpointed and spotlighted in the same way as in the more recent paintings."

Gottlieb on Color:

"I feel that I use color in terms of an emotional quality –there seems to be an emotional quality that color offers us– a vehicle for the expression of feeling. Now what this feeling is something I probably can't define, but since I eliminated almost everything from my painting except a few colors and perhaps two or three shapes, I feel a necessity for making the particular colors that I use, or the particular shapes, carry the burden of everything that I want to express, and all has to be concentrated within these few elements. Therefore, the color has to carry the burden of this effort."

"One of the characteristics of great colorists like Titian is that they use very few colors. You can count the colors - very few. The worst colorists, to my mind, use all the colors it is possible to buy. I think by the same token the artists we consider great draftsmen also use just a few simple forms. I think the worst art is that which overextends itself. Instead of exploring a simple thing profoundly, it covers a vast territory in a superficial way. It's partly modesty that I limit myself and also partly I feel I can go a lot further by exploring and by limiting the area I limit I explore and concentrate in - pinpointing and focusing on the particular thing I'm interested in, whether it's a shape or a color and I think this produces the best results, so I use this method."

Gottlieb on Other Artists:

"I did a few paintings which were surrealist in the sense of being magic-realist which is perhaps a more popular notion of surrealism. I did very few of those– I didn't want to go in that direction because the concept was too derivative, that the notion was straight out of surrealism, and I didn't really want to be a surrealist any more than I wanted to be a figurist. However, I felt an affinity, I felt a certain stimulus from the surrealists' point of view. I very much admired Masson, Miro, I liked the early Dali, I liked Max Ernst."

"I think that traditionally artists have worked in what is considered to be one style throughout their lives. You can trace the development of a painter like Cezanne, for example, even though it's accepted that he was influenced by Courbet in his youth and also by Delacroix. I know that in his less mature work, he consistently worked in one style based upon an impressionist type of painting. He developed a kind of post-impressionist style in which he is identified. I think that this long-established precedent was broken by Picasso.

Adolph Gottlieb: Recent Paintings Opens in April 1963:

Adolph Gottlieb: Recent Paintings opened at the Walker Art Center in April of 1963 and was accompanied by an exhibition catalogue with a forward and essay by Friedman. Drawn from the conversation he had with Gottlieb the summer prior, Friedman wrote a highly detailed ten-page essay.

Shown: An invitation to the opening preview of the exhibition at the Walker Art Center, April 27, 1963.

Adolph Gottlieb: Recent Paintings opening, Walker Art Center April 28, 1963. Photos by Earl Chambers, Minneapolis, MN. Artwork pictured clockwise from top left: Red, Black, Gray. 1957, Exclamation, 1958, Trio 1960, Blue at Night, 1960, Aureole, 1959.

Shown: The title page of the exhibition's catalogue.

"Gottlieb's art is one of revelation rather than exposition, and his painting gives form to the tenuous. He has consistently taken risks and abandoned successful ideas in order to break through to new and more vital ones. Through the assertion of a few elemental forms throughout a long series of paintings, Gottlieb has achieved an expansive freedom. He has never permitted his painting to rest. It is imbued with tension and tendency."

– Martin Friedman in the exhibition's catalogue essay

"Dualism is the pervasive theme of Gottlieb's art, and his painting is the eloquent resolution of conflicting forces and emotions. Now he has arrived at a dispassionate worldview, dispassionate because through form and color he envisages a universe in which human emotions are fused with rudimentary physical principles–gravity, suspension, motion. In recent paintings, Gottlieb has limited himself to a few powerful forms, nuclei suspended in tension."

– Martin Friedman in the exhibition's catalogue essay

In September of 1963, the exhibition traveled to the VII São Paulo Bienal, where it was installed at the American Section of the VII Bienal do Arte Moderna. At the Bienal, Gottlieb was awarded the Grande Prêmio prize, becoming the first American artist to receive the distinguished award. You can read more about Gottlieb at the Bienal here.

Martin Friedman and the Gottliebs:

Martin Friedman and his wife Mildred (Mickey) formed a close friendship with the Gottliebs, extending into their traveling to São Paulo together. The Friedmans were gifted the painting Bastille Day (1961) as a thank-you for the organization of the Walker Art Center exhibition and their further support at the São Paulo Bienal. Below are their notes of appreciation.

"Everyone who visits us is knocked out by the beauty of the painting and reactions run from amazement to sheer envy -- why not?" – Martin Friedman

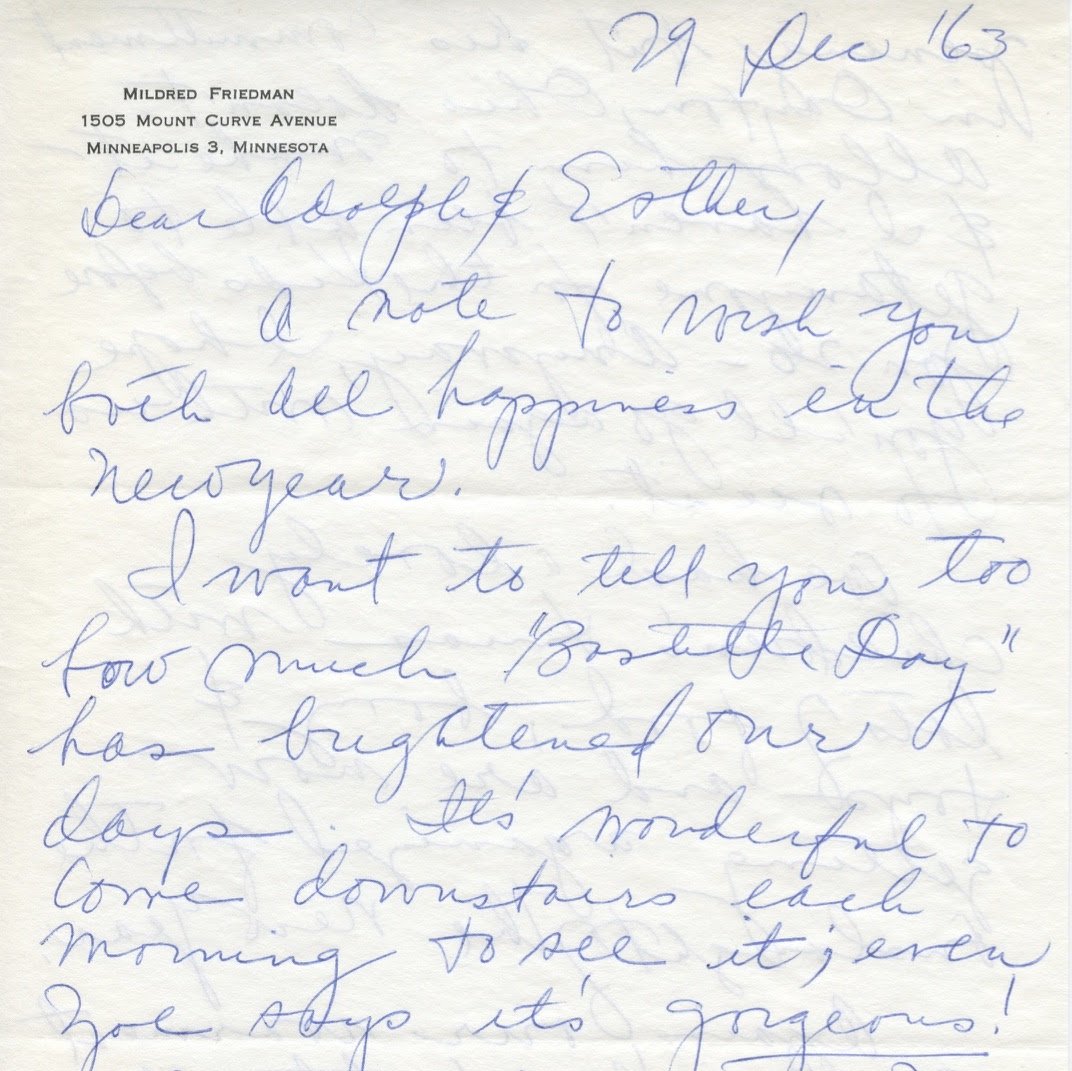

"I want to tell you how much "Bastille Day" has brightened our days..." – Mickey Friedman

Shown: Photo of Bastille Day (1961) at Martin Friedman’s home, 1964.

Shown: Color image of Bastille Day, 1961, oil on canvas, 48 x 72"

Shown: A thank you letter to Adolph Gottlieb from Martin Friedman for his gift of Bastille Day (1961), December 6, 1963.

Shown: A thank you letter from Mildred Friedman to the Gottliebs emphasizing their love of Bastille Day (1961), December 29, 1963.

Correspondence Throughout the Years:

Martin Friedman's admiration for Gottlieb's work continued through Adolph's lifetime and after the artist's death in 1974. Friedman continued his support of Gottlieb's work through the years and strove to increase the Walker Art Center's holdings of Gottlieb's work during his tenure as director.

Shown: A postcard to the Gottliebs from Martin Friedman, June 24, 1964.

In the above postcard, Martin Friedman writes of his travels in Europe and the new postcards of the Walker Art Center's best paintings that include the one he sends to Adolph and Esther of Trio (1960).

Shown: A condolence letter from Martin Friedman to Esther Gottlieb after Adolph's death, March 20, 1974.

Shown: A letter to Esther Gottlieb from Martin Friedman, February 14, 1981.

"Adolph raised my sights artistically and helped me to understand not only his art but that of his particularly gifted generation. The experience of working with him remains a happy part of our lives."

– Martin Friedman in a condolence letter to Esther Gottlieb, March 1974

"Although there has been a lapse in our communication, there has never been one in my admiration for Adolph Gottlieb's accomplishments as a major American artist. In the long view, those accomplishments are what we want to recognize by adding some key works to the two fine Gottlieb paintings in our permanent collection, "Trio" and "Blue at Noon."

– Martin Friedman in a letter to Esther Gottlieb, February 1981

Shown: Trio, 1960, oil on canvas, 60 x 90", Walker Art Center