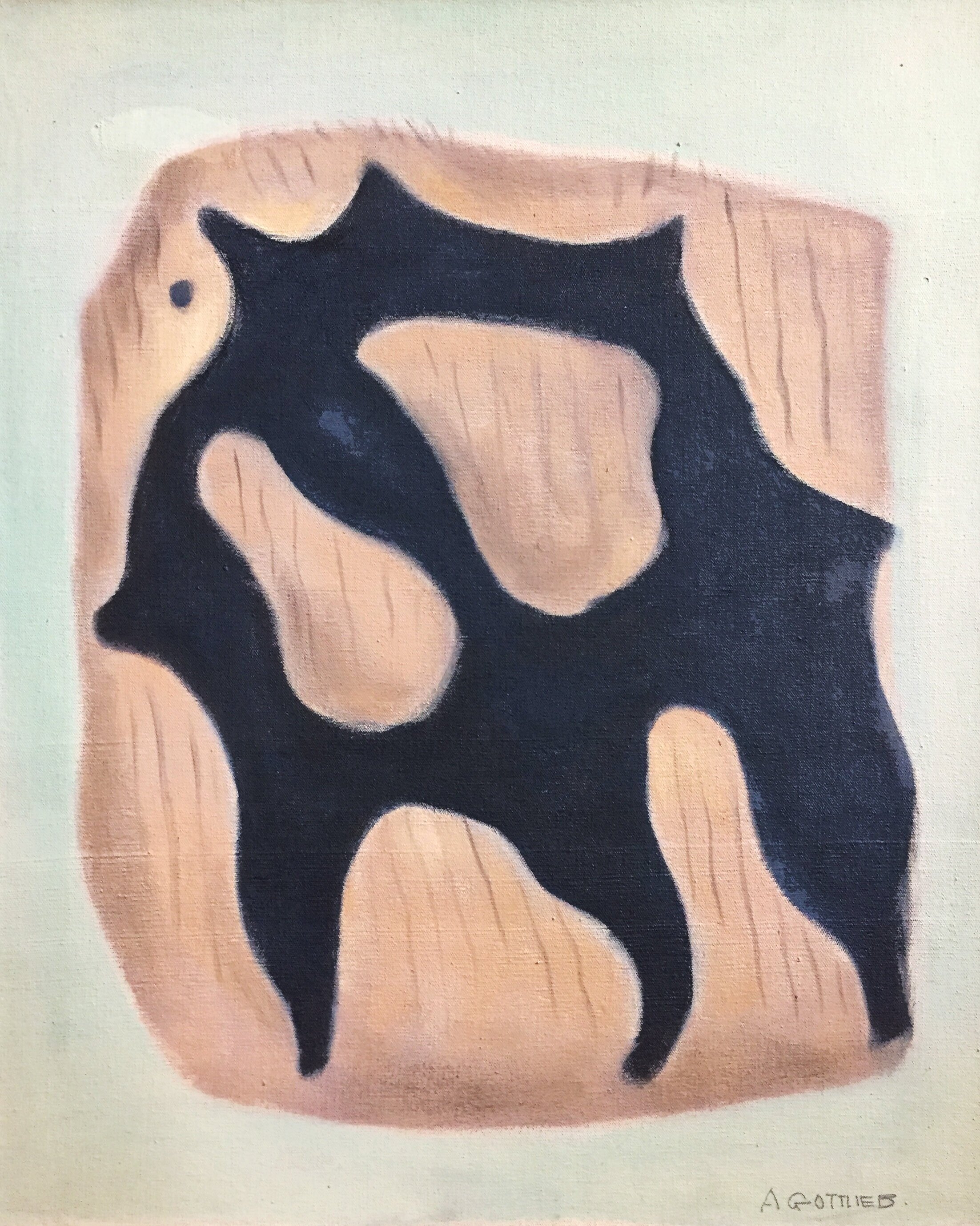

Adolph Gottlieb, The Rape of Persephone, oil on canvas, 33 x 25"

Currently in the collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College

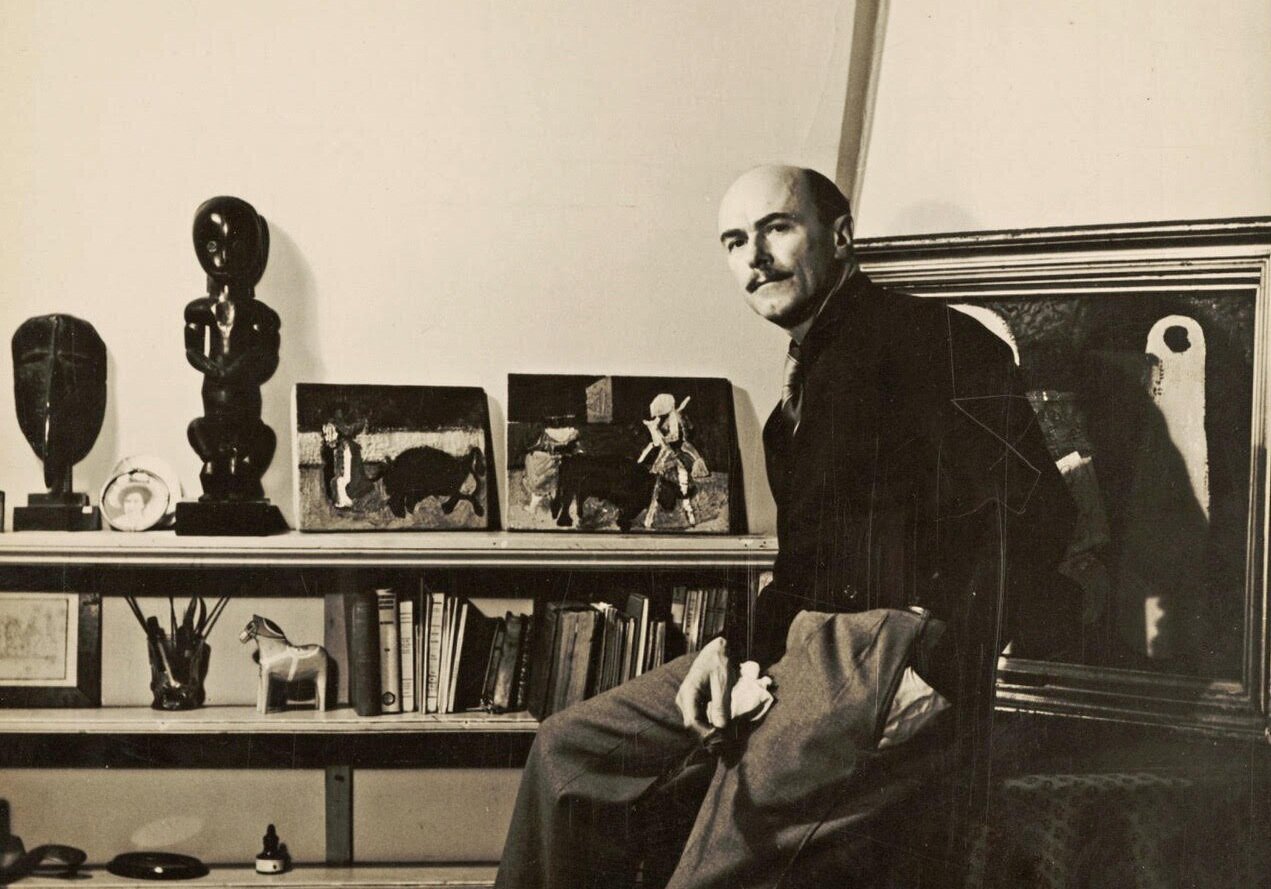

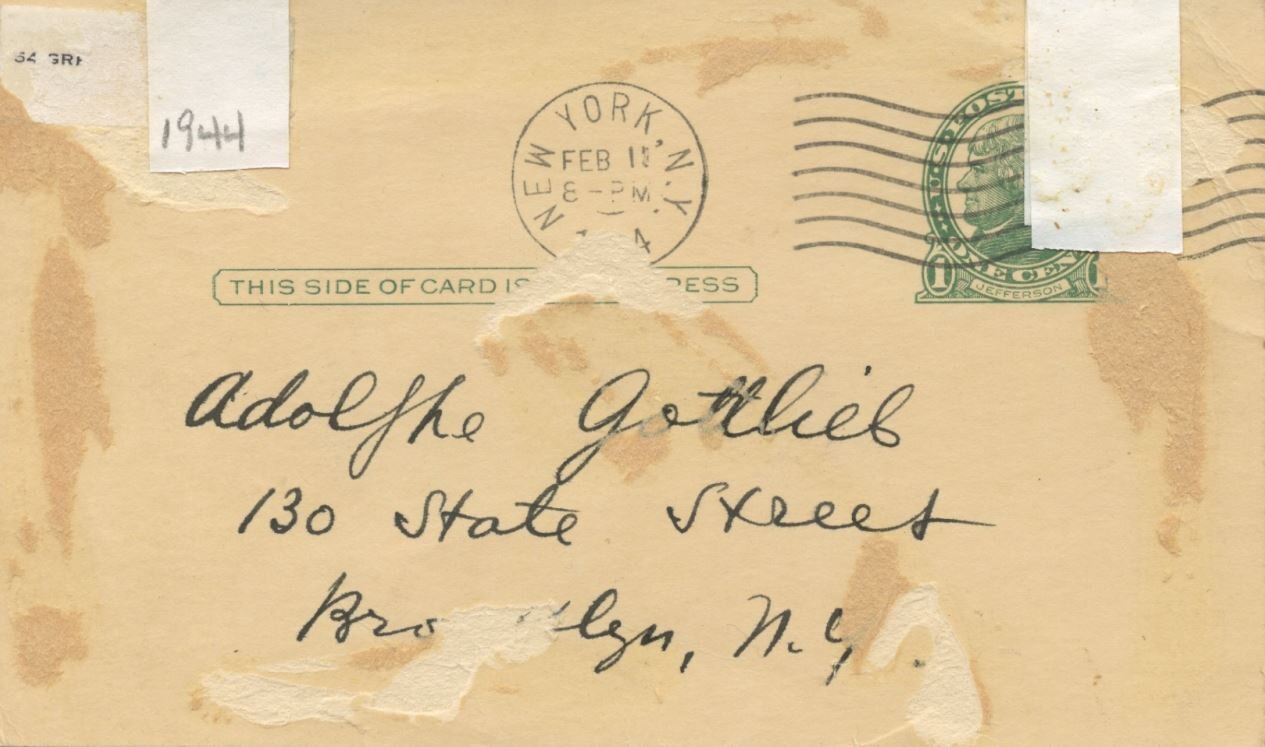

In June 1943, Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko exhibited their new paintings in a large exhibition of the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. This was the largest exhibition, and one of the earliest, to show one of Gottlieb's Pictographs as well as one of Rothko's mythic paintings.

Edward Alden Jewell, senior critic at the New York Times, published a lukewarm review of the show but paid special attention to Gottlieb and Rothko. Of Rothko's and Gottlieb's paintings specifically, Jewell writes, "You will have to make of Marcus Rothko's 'The Syrian Bull' what you can; nor is this department prepared to shed the slightest enlightenment when it comes to Adolph Gottlieb's 'Rape of Persephone.'"

In response, Rothko and Gottlieb decide to pen a letter directly to Jewell. Each artist drafted his own response and they then sat down together to combine them into a single letter. They reviewed that draft with their colleague Barnett Newman, who they thought of as a writer, to help shape a final version which was signed by Gottlieb and Rothko and delivered to Jewell. The artists write, "We do not intend to defend our pictures. They make their own defense. We consider them clear statements. Your failure to dismiss or disparage them is prima facie evidence that they carry some communicative power."

The letter enumerates 5 aesthetic beliefs that were central to the artists' new direction:

To us, art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take risks

The world of the imagination is fancy-free and violently opposed to common sense.

It is our function as artists to make the spectator see the world our way--not his way.

We favor the simple expression of complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.

It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.

These ideas precede any discussion of what we think of as Abstract Expressionism by years. But the ideas expressed in this letter were fundamental to the Abstract Expressionist movement.

Jewell incorporated these statements in his response published a week later (The New York Times, June 13, 1943).

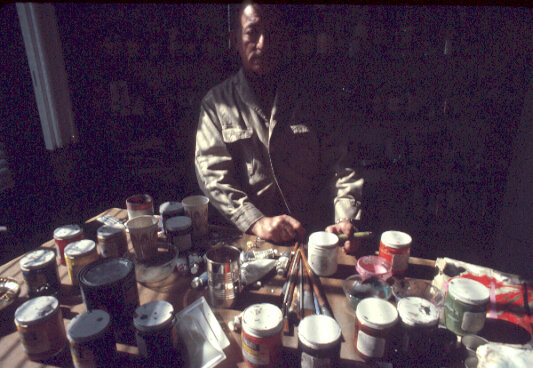

Pictograph-Symbol, oil on canvas, 54 x 40"

Currently in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago

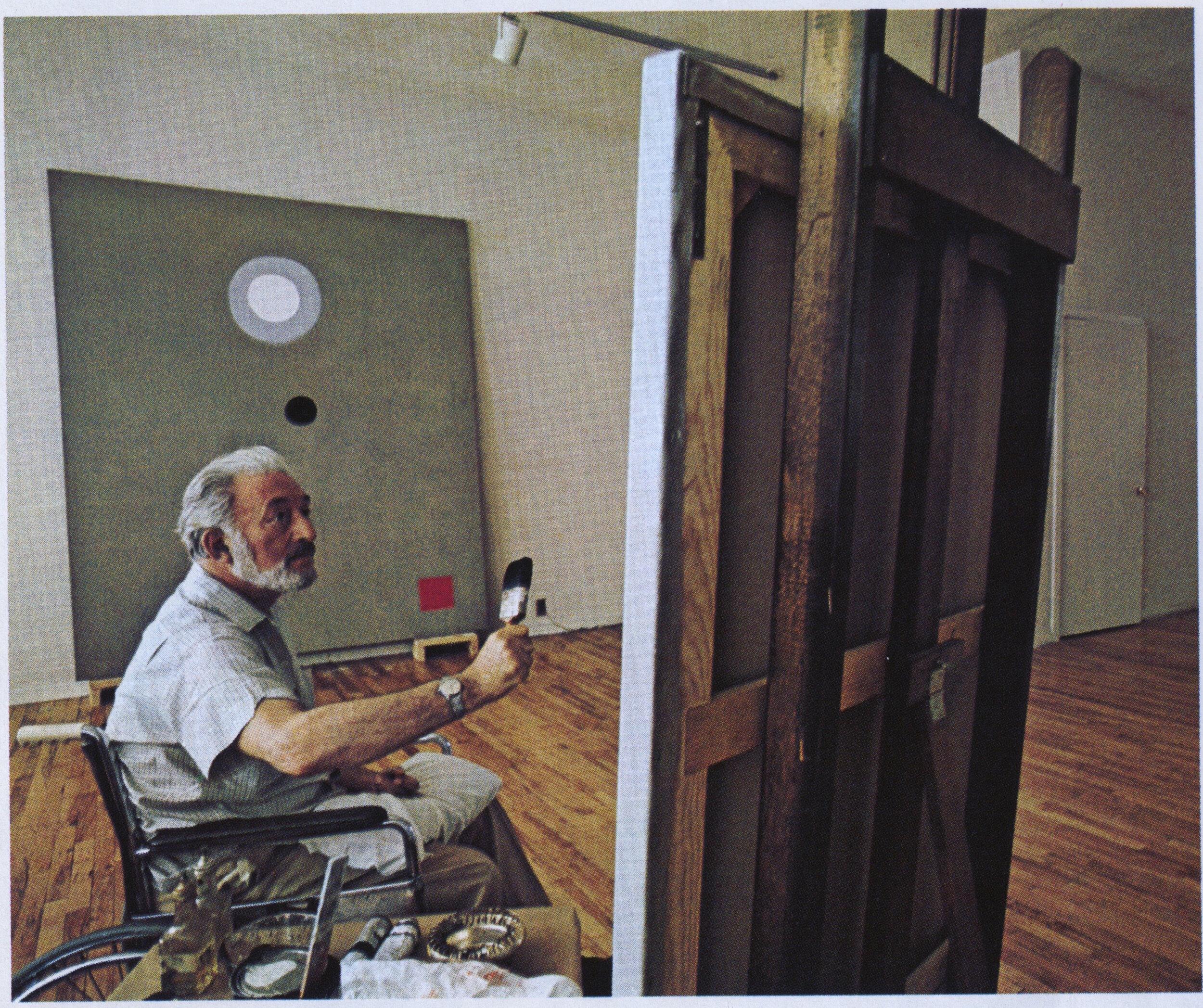

In October of that year, in a radio interview of Rothko and Gottlieb, Gottlieb defends their use of myth and abstraction in their paintings, presumably informed by their exchange with Jewell:

Everyone knows that Grecian myths were frequently used by such diverse painters as Rubens, Titian, Veronese and Velasquez, as well as by Renoir and Picasso more recently.

It may be said that these fabulous tales and fantastic legends are unintelligible and meaningless today, except to an anthropologist or student of myths. By the same token the use of any subject matter which is not perfectly explicit either in past or contemporary art might be considered obscure. Obviously this is not the case since the artistically literate person has no difficulty in grasping the meaning of Chinese, Egyptian, African, Eskimo, Early Christian, Archaic Greek or even pre-historic art, even though he has but a slight acquaintance with the religious or superstitious beliefs of any of these peoples

The reason for this is simply, that all genuine art forms utilize images that can be readily apprehended by anyone acquainted with the global language of art. That is why we use images that are directly communicable to all who accept art as the language of the spirit, but which appear as private symbols to those who wish to be provided with information or commentary.

– Adolph Gottlieb, "The Portrait and the Modern Artist," from a broadcast on

"Art in New York," Radio WNYC, October 13, 1943.

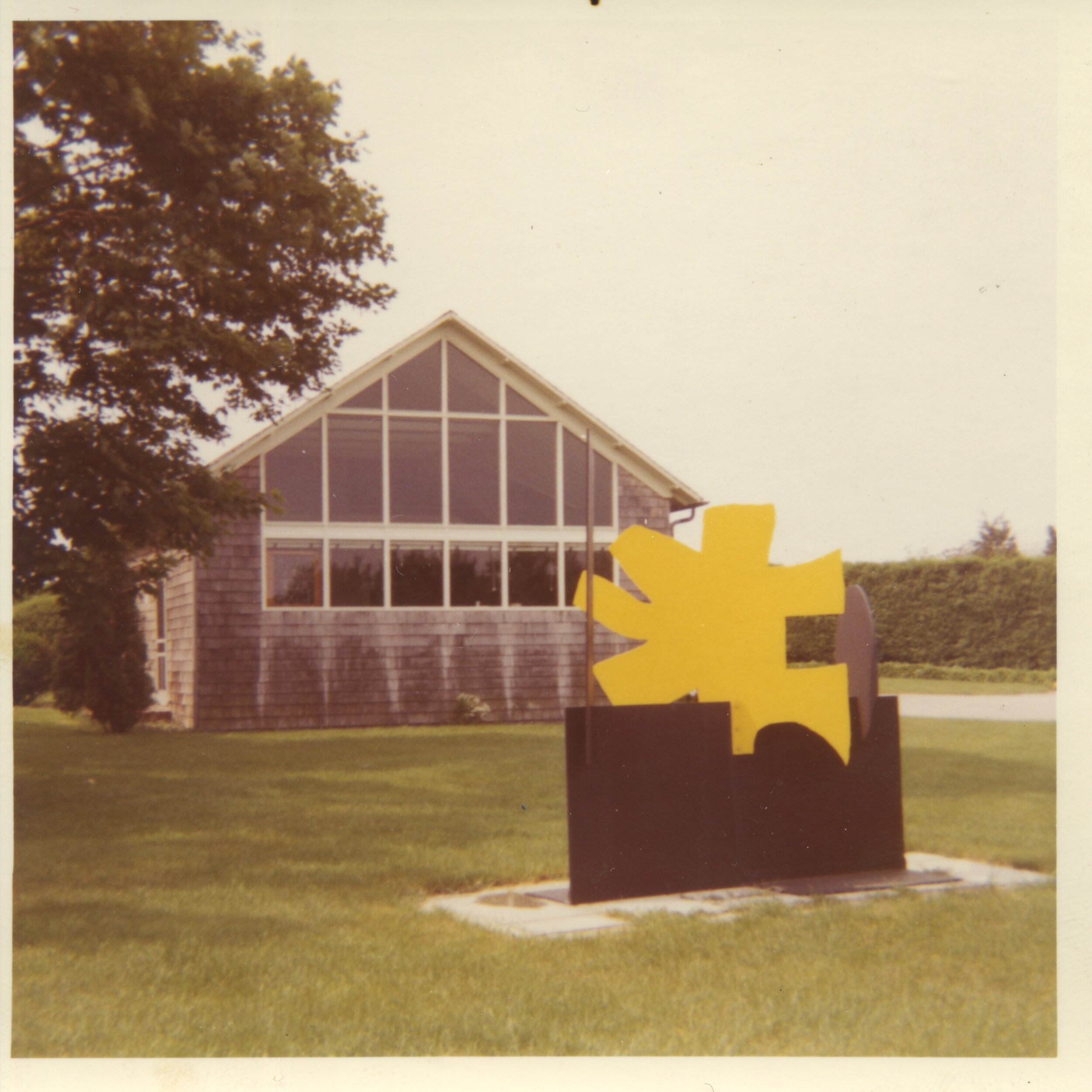

Pictograph, oil on canvas, 47 3/4 x 35 1/2"

Currently in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC

Pictograph, oil on canvas 35 15/16 x 24 7/8"

Currently in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art