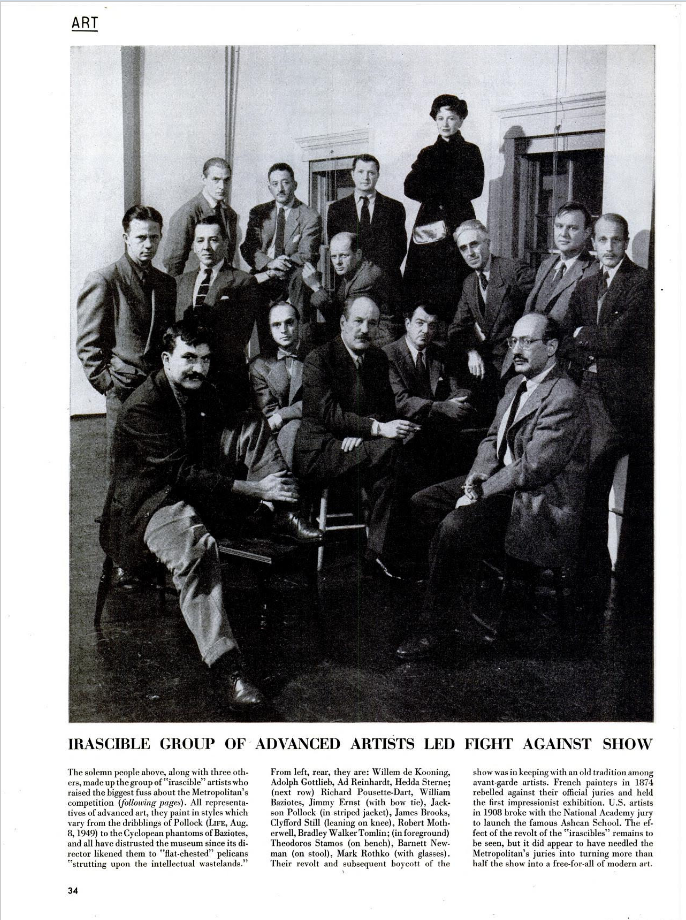

Adolph Gottlieb and Mark Rothko began regular discussions about their dissatisfaction with the art of their times around 1938 – that is, around the time of the Civil War in Spain. By 1941, these talks resulted in profound changes in the art they both made. brutal images from the real world were overtaking images in the arts. Neither the peaceful harmonies of the American scene nor the intellectual mysteries of Dali and the Surrealists could come to terms with the daily realities of the Second World War.

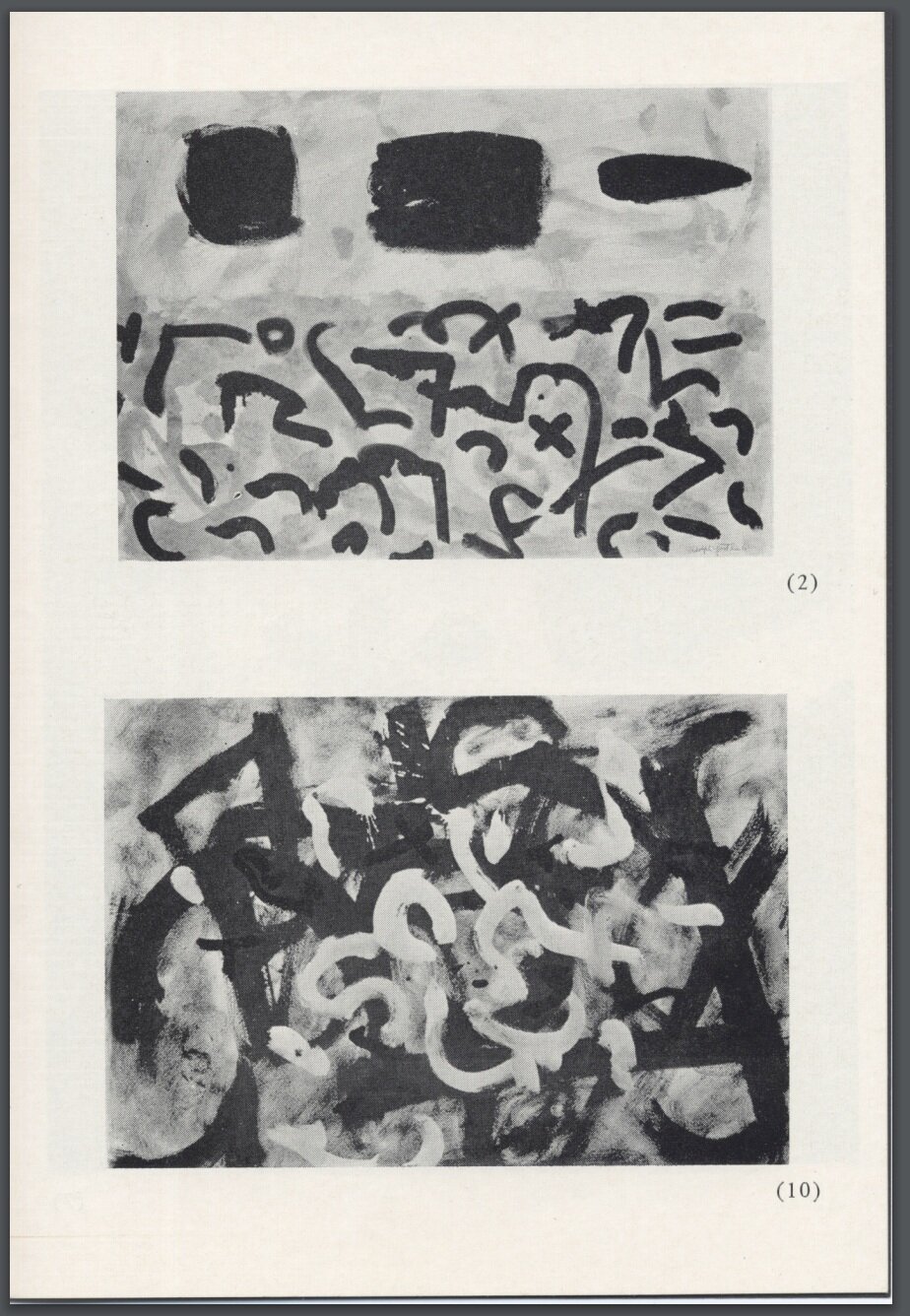

Gottlieb began the paintings he labeled Pictographs that year, when the Great Depression had not yet ended and WWII was raging throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia, and was fast approaching the U.S. Pictographs were a huge leap for Gottlieb, 20 years into his career as a painter. At that moment, he abandoned his established methods for a new approach to art: “My whole conception is primitive – of a certain brutality. I think life is a mixture of brutality and beauty.”

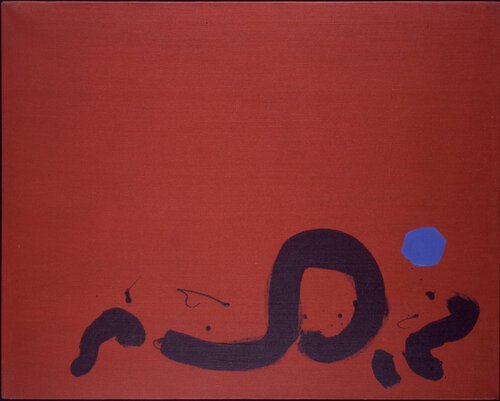

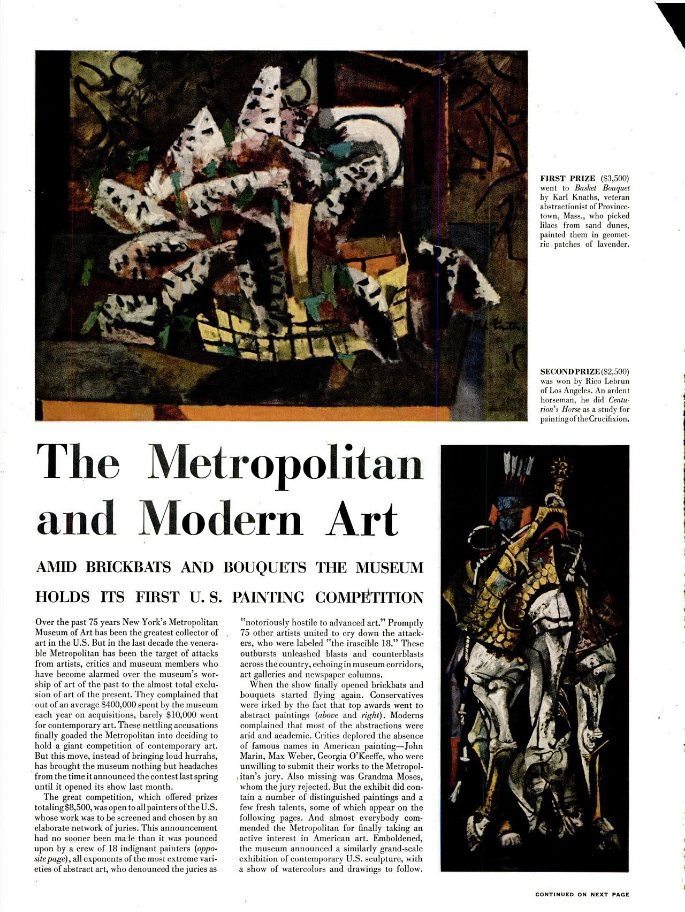

Adolph Gottlieb, Black Enigma, 1946, oil on canvas, 25 x 32 in.

The breakthroughs of each artist are significant to the development of what we think of as Abstract Expressionism. After they agreed to work from Classical themes, Gottlieb developed his Pictographs and Rothko originated what have been termed his mythic paintings. As Gottlieb described the situation, "We very quickly discovered that by a shift in subject matter we were getting into formal problems that we hadn't anticipated. Because obviously we weren't going to try to illustrate these themes in some sort of Renaissance style. We were exploring. So, suddenly we found there were formal problems that confronted us for which there was no precedent, and we were in an unknown territory.”

Adolph Gottlieb, Hands of Oedipus, 1943, oil on linen, 40 x 35 15/16 in.

Adolph Gottlieb, Eyes of Oedipus, 1941, oil on canvas, 32 1/4 x 25 in.

Gottlieb forged a visual synthesis of the emotional, cultural, and historic implications of the Oedipus myth and its uses and influence. Gottlieb and Rothko, in beginning new directions, returned to the sources of Western art. But they did so in a way that aimed to re-connect with what they saw as a more universal basis for visual art. The fundamental issue for these two artists, and one that became common among their colleagues, was a belief in the ability of visual images to convey meaning - to be emotionally charged and engaging - without the usual structure of narrative, whether literal or symbolic. As Gottlieb stated in a 1968 interview with Lawrence Alloway, "so if I made paintings in ’41, and in the ‘40s, that looked as if I didn’t know anything about art, it wasn’t really that I didn’t know, it was that I was struggling and trying to find something to say that was meaningful in a personal way, and also in sort of a fresh way, which wasn’t… which didn’t conform with the ideas of the establishment."

Adolph Gottlieb, Pictograph - Symbol, 1942, oil on canvas, 54 x 40 in.

In the absence of narrative, the physical presence of the painting became a major determinant of how it was viewed. Gottlieb created his Pictographs to appear rough and unfinished. This was part of his concept of a painting as a dialogue with an individual - the understanding that the work is complete only with the participation of the viewer. The conceptual bases of these paintings - immediacy, non-narrative subject, intuitively derived composition, the importance of process, the notion of painting as object, and an acceptance of viewer as contributor, were shared by virtually all of the artists who became known as Abstract Expressionists. They take us, in Gottlieb’s words, “to the beginning of seeing.”

Adolph Gottlieb, Composition, 1945, oil, gouache, casein and tempera on linen, 29 13/16 x 35 7/8 in.

Gottlieb and Rothko were responding to a debate among American artists about meaning and abstraction. In their responses, given the very uncertain world in which they lived, they were also attempting, in a sense, to re-capture the thread of culture from the chaos of war. That is a large, perhaps even grandiose, goal. It was a big and important venture at a time when everything was in chaos and they had nothing to lose. But it is in keeping with the way American artists of that generation saw the potential of art.

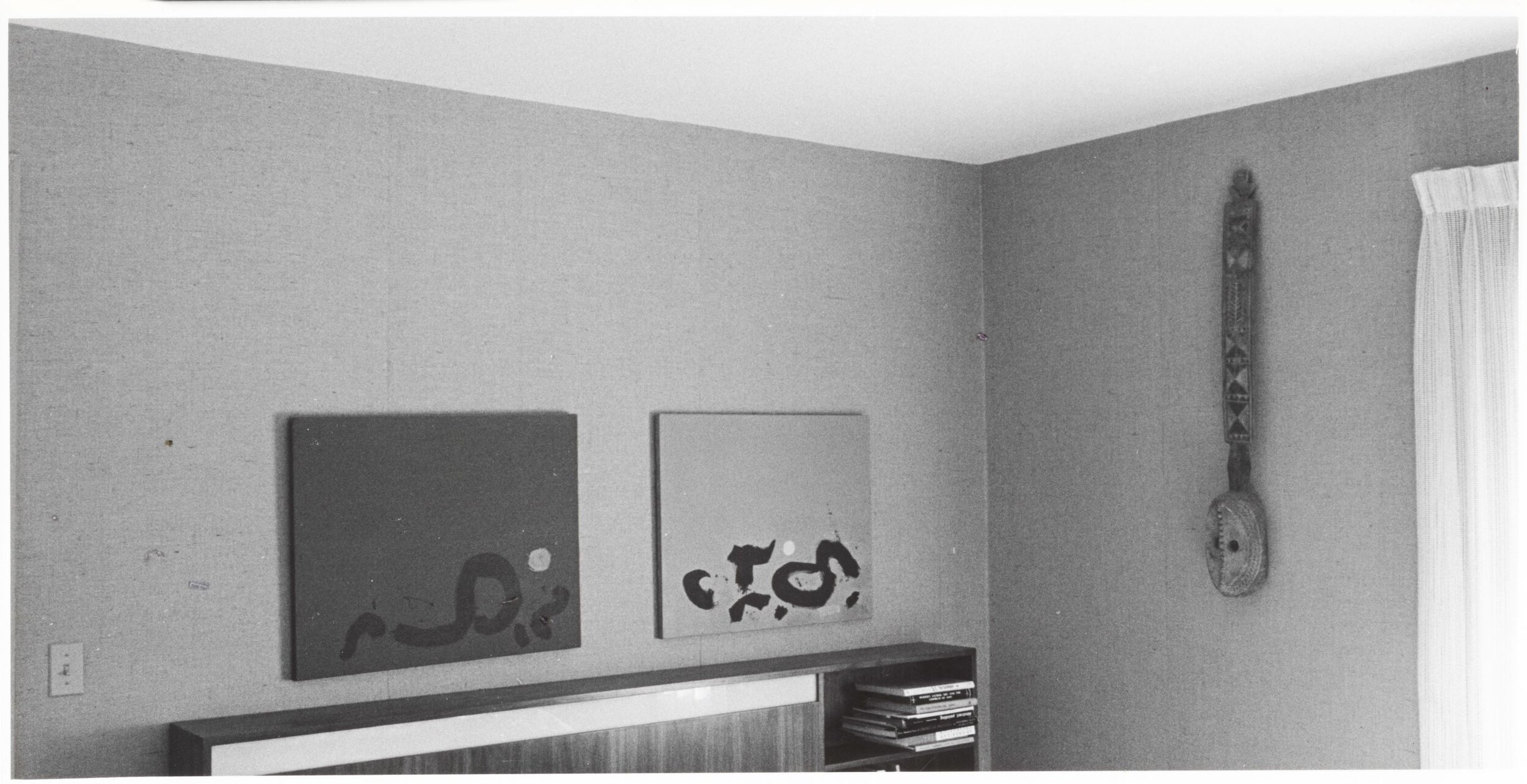

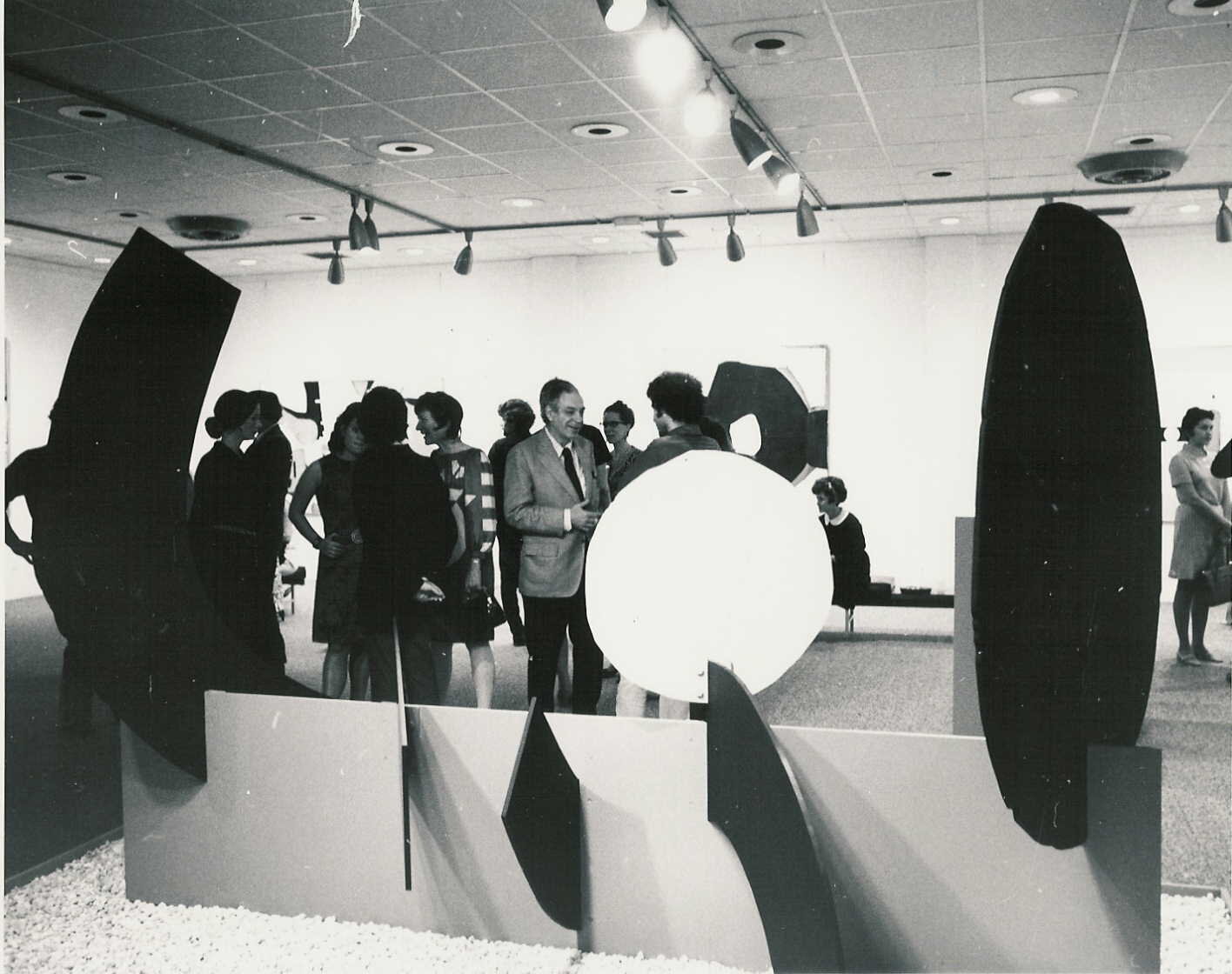

Adolph Gottlieb in his home/studio in Brooklyn with paintings including

Reflection (1941) and Pictograph (1942), 1942. Photographer: Aaron Siskind.